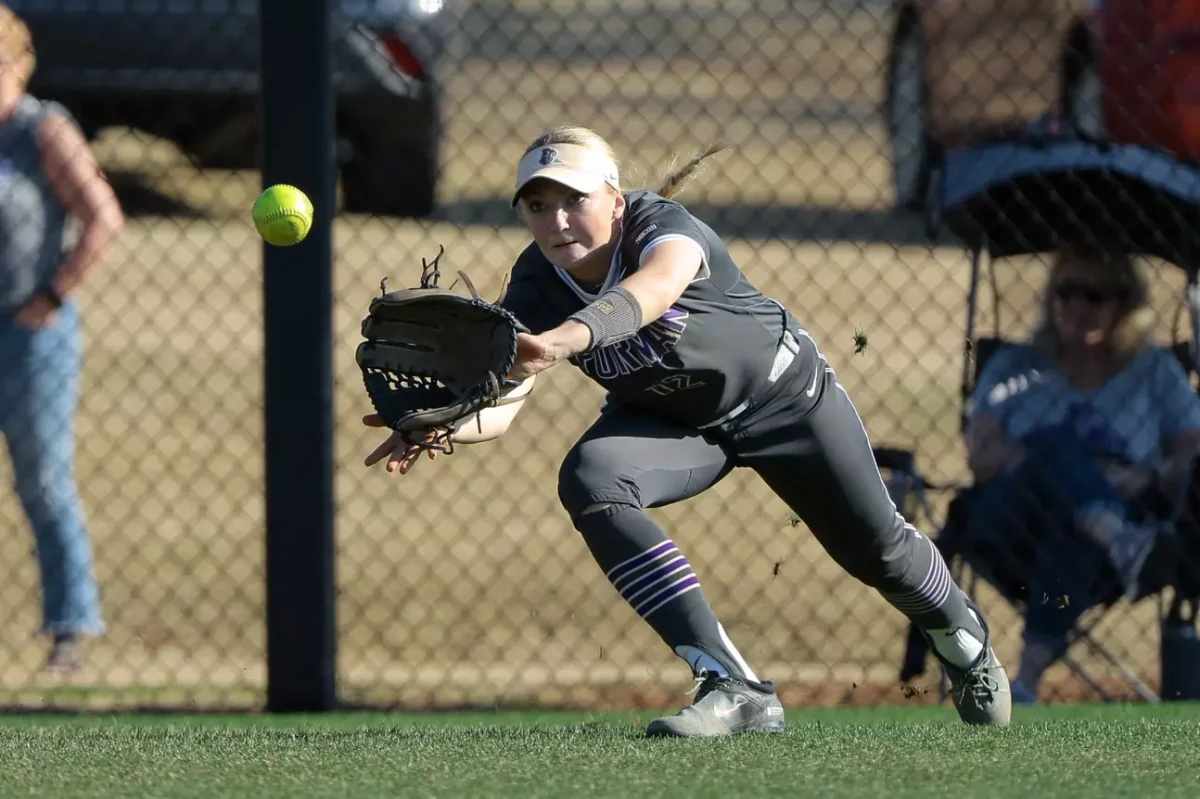

Many liberal arts campuses, such as Furman, have enclosed campuses where students live for all four years. The insularity these campuses create, which students here have called the “Furman bubble,” keeps us from engaging with our wider community on a daily basis. We can drive to coffee shops and restaurants, but we tend to only enjoy the city when it is convenient for us. We do not live in Greenville — we live at Furman.

The campus is a uniquely American invention, according to an article in TIME Magazine. The original purpose of keeping students in an enclosed area was to protect their virtue because cities were thought to have the potential to “corrupt” minds. Although we have come a long way from this close-minded ideology, the limitations of an enclosed campus remain.

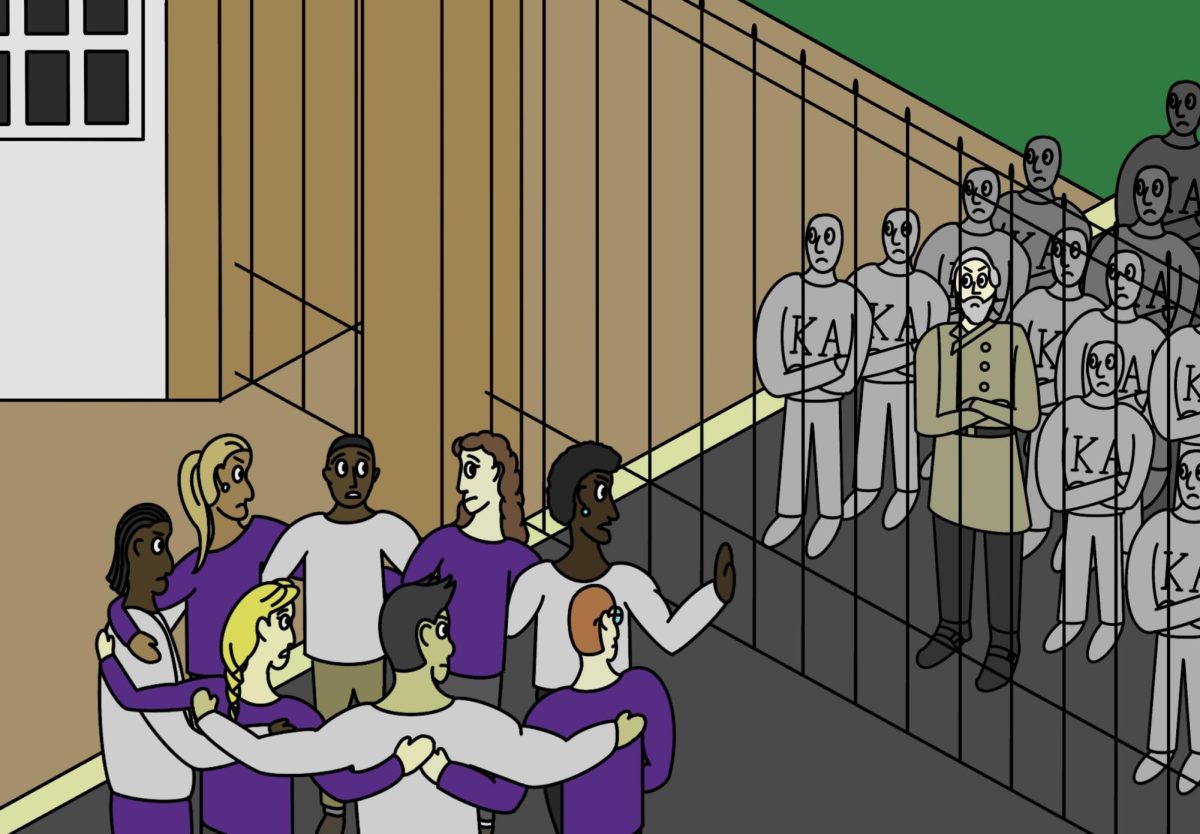

Furman’s mission statement states, “We cultivate discovery, collaboration, civic engagement and the exchange of ideas through innovative programs and a diverse residential community experience.” But on an enclosed campus, this community experience can only be as diverse as our student body.

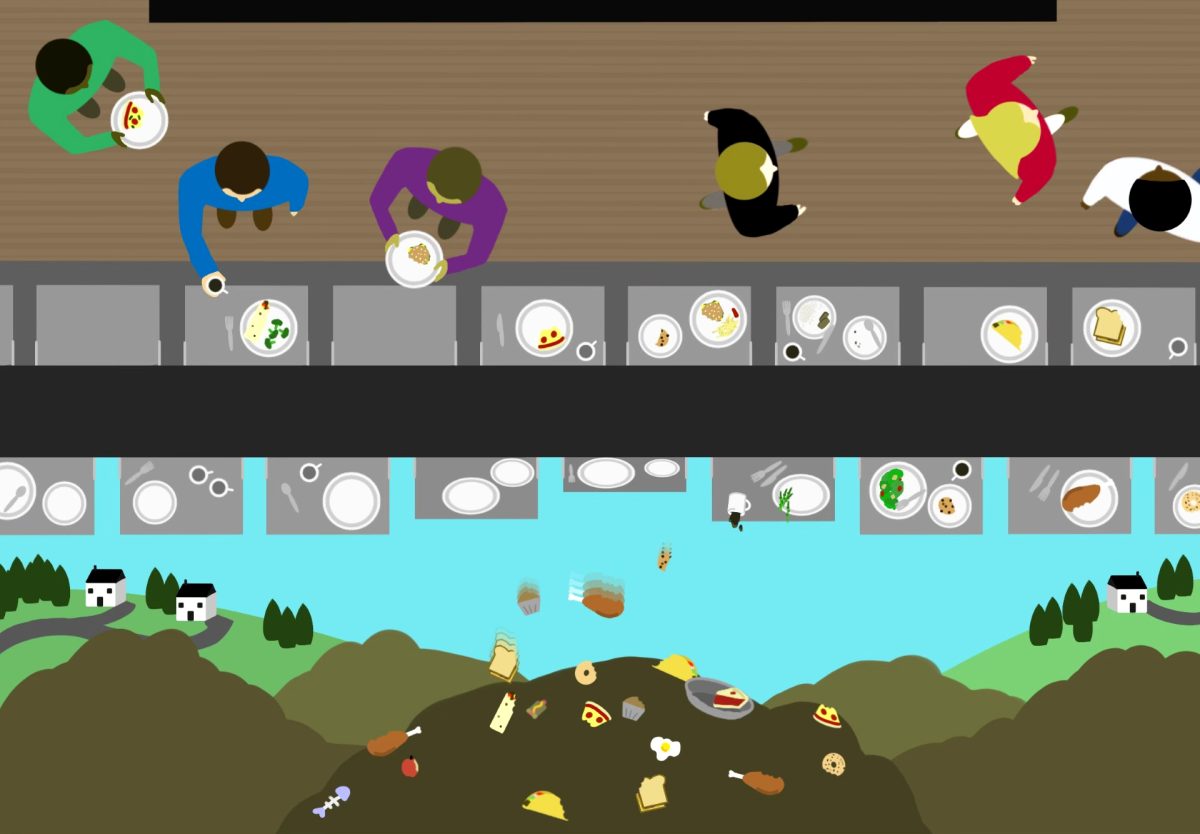

According to The New York Times, 71% of our students come from the top 20% with a median family income of about $180,000. For the average family in Travelers Rest, that number is a mere $36,000. We are surrounded by mostly upper-class students and insulated from a darker socioeconomic reality just down the road. As Paladin writer Courtney Kratz pointed out in 2018, “Furman’s economic homogeneity incubates a particular view of the world. We normalize wealth to such an extent that we fail to fully recognize it as wealth.”

As a highly resourced college in the Greenville area, we have a unique opportunity to learn from, serve, and take part in this community, but we rarely do. Furman’s presence in the rest of Greenville is limited, though it should be the place where we are applying everything we learn.

“The elite American university today is a paradox: Even as concerns about social justice continue to preoccupy students and administrations, these universities often seem to be out of touch with the society they claim to care so much about,” Nick Burns wrote in the New York Times’ article “Elite Universities Are Out of Touch. Blame the Campus.”

So, how are we as Furman students supposed to deal with this problem if we cannot change the structure of our campus?

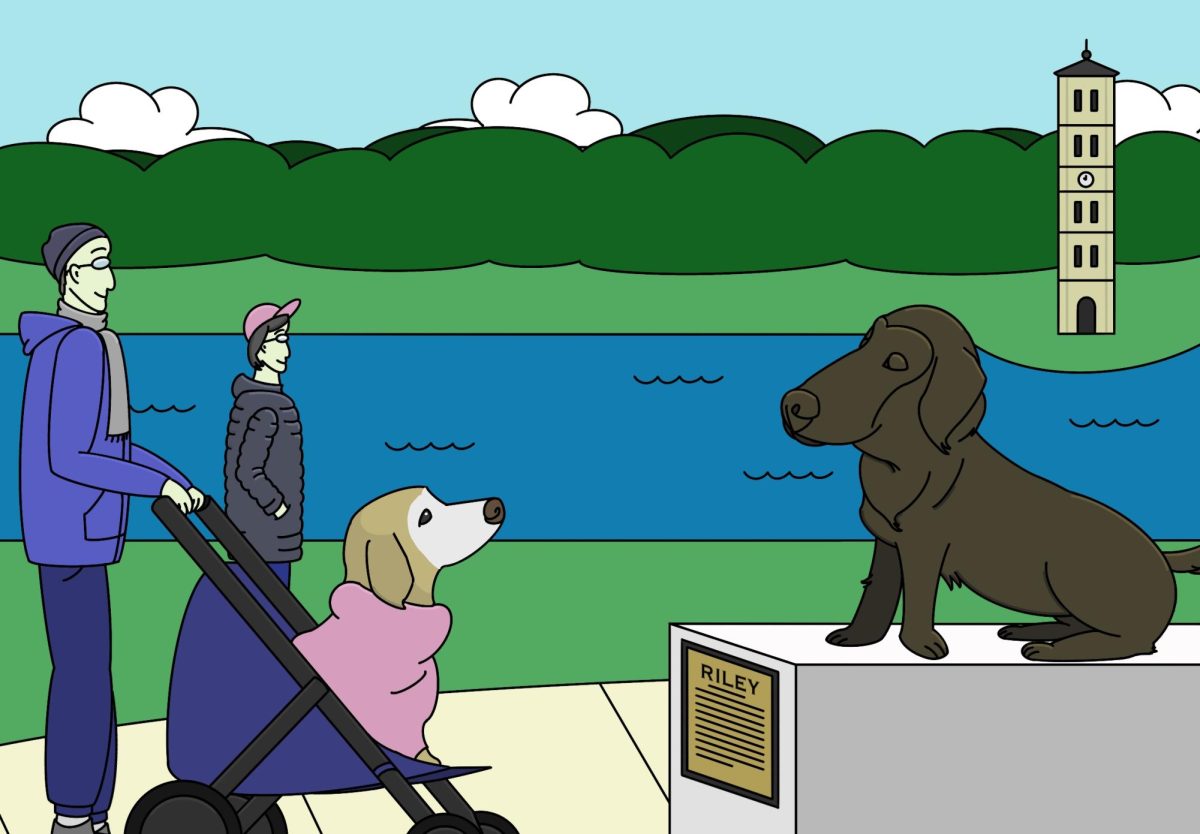

First off, we should appreciate, rather than gripe about, the ways Greenville integrates with our campus. We often jump to conclusions that so-called “townies” shouldn’t be using our campus resources. But without them, we are even more isolated. People like Dave and Kathy Knox, the owners of Riley the dog, bring students daily joy and interaction with the outside world. We should welcome more people this way, recognizing that they are our entry points for connection with the Greenville community.

While Furman does place an emphasis on beyond-the-classroom learning, this focus is often lost in the typical semester due to our isolation and over-involvement in on-campus activities. These enriching off-campus experiences are often saved for summers when we are already off-campus. But if we fail to venture beyond the Furman gates while we are living here, we will lose touch with our own city — the most vital community for us to understand.

To combat this, we should expand our view of extracurricular activities to off-campus opportunities in order to apply what we are learning about the world and better our community.

If students do not have the time to dedicate themselves to service, they can still take advantage of times when the Greenville community comes to them. For example, the South Carolina Supreme Court came to McAlister Auditorium recently, giving students a rare opportunity to observe the judicial process. While these events could be more frequent to balance out Furman’s isolation, it is important that students take advantage of them when they happen to expand their perspective of Greenville.

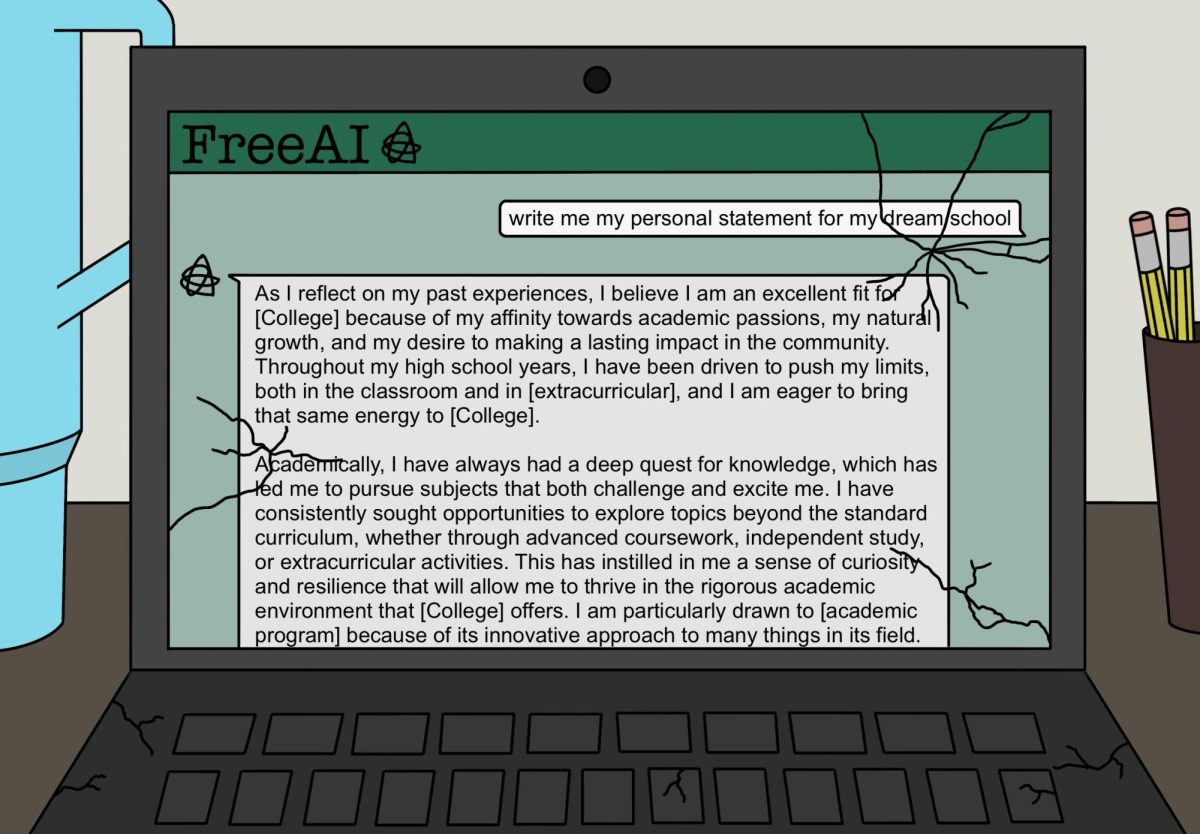

In his commencement address to Kenyon College in 2005, writer David Foster Wallace advocated for the necessity of building critical thinking skills through the liberal arts experience. However, he also noted an innate flaw in the academic setting. He said, “The most dangerous thing about an academic education is that it enables my tendency to over-intellectualize stuff, to get lost in abstract thinking instead of simply paying attention to what’s going on in front of me.”

At Furman, some of the biggest issues in the world are not in front of us. They are taught in the abstract. And without a real-world community to apply them to, there they will remain.

It is our job to put ourselves face-to-face with the world’s injustices. To refuse to be satisfied with a blissful life on our picture-perfect campus. To instead come to terms with what it has helped us ignore.