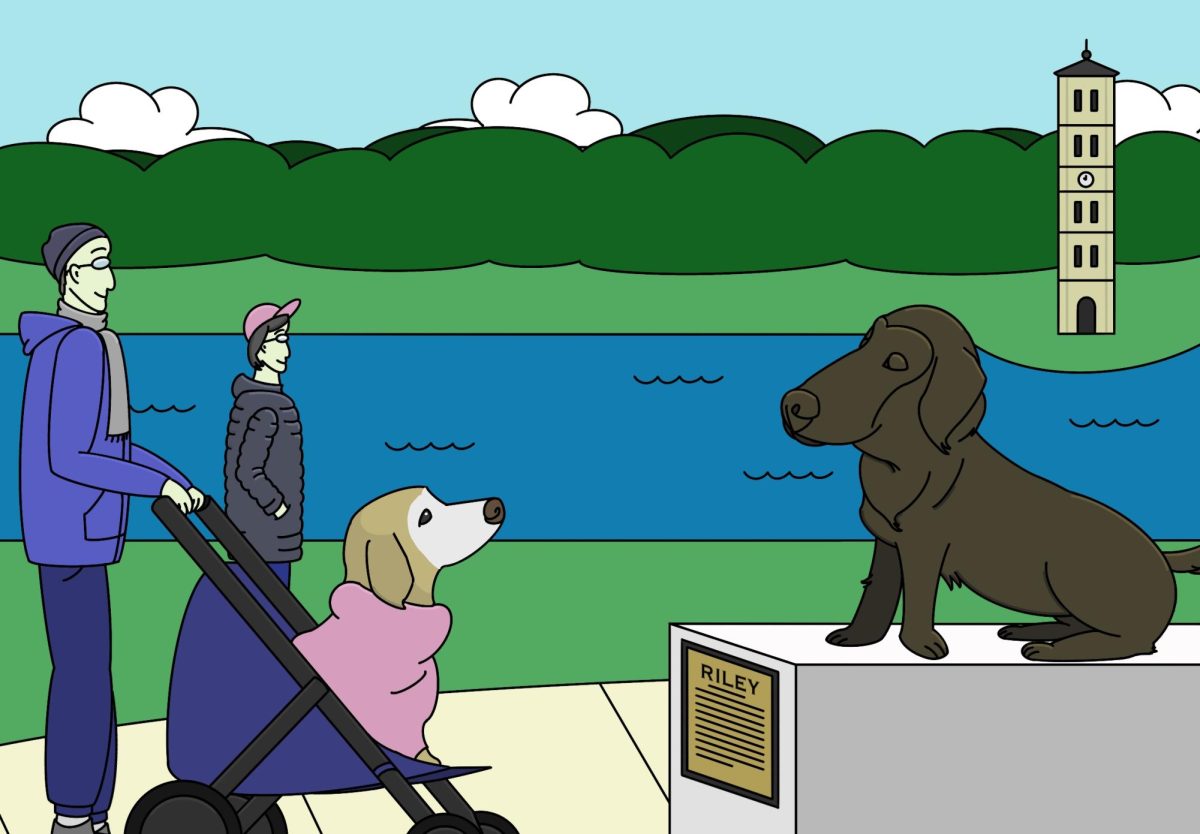

On Monday, Sept. 25, the campus community received a mass email asking that all vehicles be kept off Furman lawns. The reason? A lawncare practice called “overseeding,” which involves irrigating existing grass fields, re-seeding, potentially fertilizing, and watering 3-4 times a day so the new seeds can germinate in the existing turf. The email has enlivened a debate over the value of grass lawns on campus and in society. Where did they come from? What do they cost? And is the grass really greener when we cut it?

The turf lawn, those ubiquitous trimmed expanses, are a mainstay in universities across the United States. And just as they define Furman’s landscape today, they have been the symbolic definition of the so-called “American Dream” and middle-class exceptionalism for centuries, even dating back to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello Plantation, according to Pennington Lawn. But their origin is far more elitist in nature than the imaginary green lawn and white picket fence.

The first turf lawns were popularized by the European aristocracy, who maintained the labor and resource-intensive fields as symbols of their wealth and power, according to Garden Illustrated. In an era before motorized landscaping devices, scythes were the primary tool used by workers, requiring great skill and expense. Further, the act of using people to keep a neatly trimmed field for aesthetic purposes rather than for feeding livestock was a particularly pretentious and wasteful display of means. This is the tradition that those green behemoths that mark our grounds inhabit.Philosophical considerations aside, lawns have a tangible negative impact on our environment today. In addition to being described as “ecological dead space” by the Washington Post, consider the following facts, according to Pale Blue Dot and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Specifically at Furman, every vegetated acre of campus consumes, on average, 263,925.89 gallons per year, according to The Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System. Synthetic fertilizer and pesticide use further contributes to the university’s carbon footprint and impact on native biodiversity. Though this number has decreased from 336,657.14 gallons per acre to 263,925.89 gallons per acre, (a reduction of 21% since 2004) it’s worth questioning how low it can really go. After all, it doesn’t take a sustainability major to recognize that turf monoculture isn’t the natural flora of upstate South Carolina – some amount of human maintenance or manipulation will always be required, no matter how “green” it looks.

The beauty of Furman’s campus is an integral part of our culture and our appeal as a school, but who gets to decide what is beautiful? If our standard of natural beauty comes at the expense of nature, it’s probably worth re-examining that standard. And for a school that seeks to serve as a model of sustainability, what kind of message do our lawns send to those who aspire to live within our environment’s means, and to outsiders who revere Furman’s focus on the environment.

If we really want our campus to look its best for the fall and winter, it might be worth reimagining what sustainable landscaping can look like. It could take incorporating native carbon-negative trees and shrubs, designating “No-Mow” zones, or rebuilding a flora that can sustain a biodiverse ecosystem. Our campus’ grass might not look greener on the other side of our environmental goals. But if sustainability really is more than a buzzword at Furman, it’s time to start making the sacrifice for a better future.