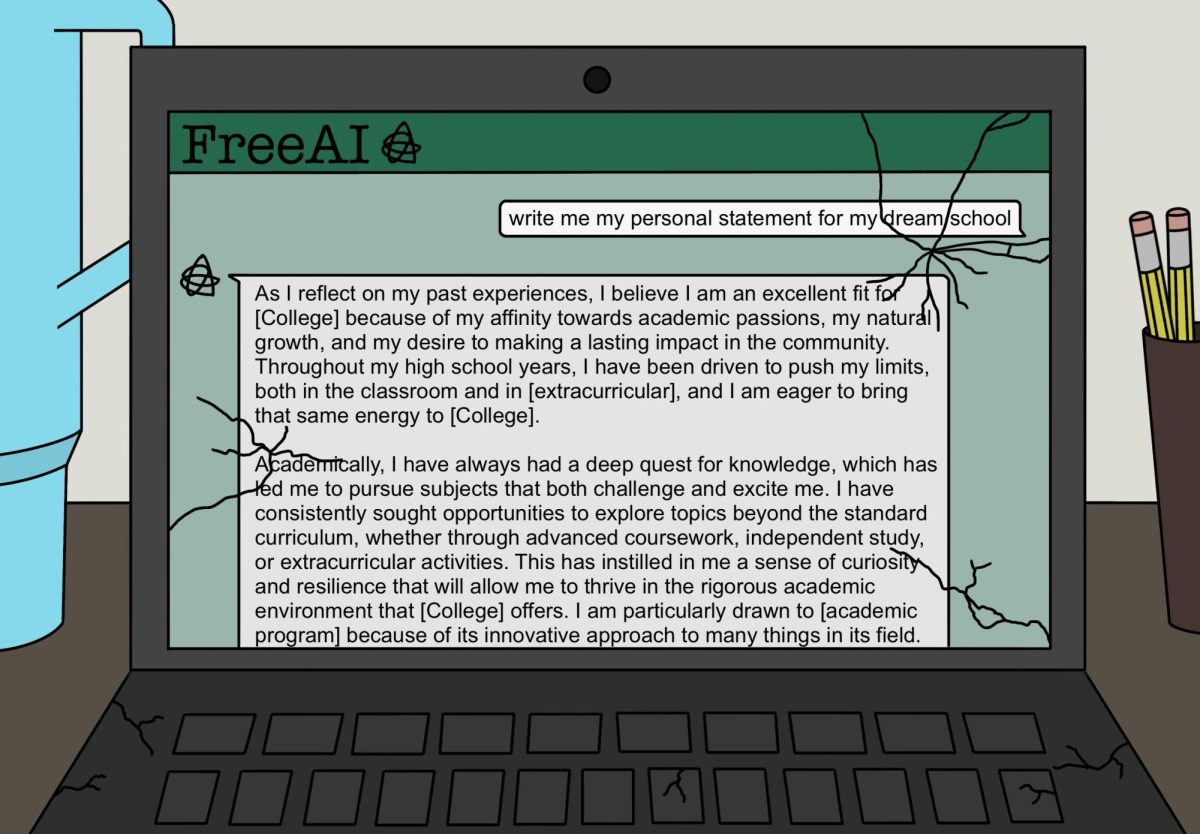

ChatGPT, OpenAI’s newest addition to our ever-growing AI menu, has prompted cheating concerns and integrity cases on campuses across the country. Forget a machine that corrects your work; this machine completes the work for you, and does a good job. Dr. Hick of the Philosophy Department caught a student using the service to write an essay last semester and posted a warning for other professors on Facebook. As you can imagine, this gained traction and quickly grew into interviews with press like CNN and NYPost.

The implications of this chatbot on academic integrity are clear, but what about its effect on us? What does technology like ChatGPT, available for all on the market, strip from students by giving us what we want? Is it a fair trade?

In a conversation squeezed between other press interviews, Dr. Hick answered these questions by asking another: “What is education good for?” Or in other words, why am I using this product?

People might have grappled with the same issue when the first calculator came out. What is math good for? Finding solutions! Why do we do math? To get an answer! Why should I use a calculator? Because I can get there more effectively.

Seems straightforward. Math is an arguably product-oriented business; I don’t get good at math to be a great mathematician, I do it to find answers and to solve problems that are applicable to everyday life. But what about writing? What is writing good for? Why do we write? Why should I use ChatGPT, the fanciest new calculator?

Things get complicated here. If you are writing an essay solely to have an essay, get a grade, get a degree, get a job, get money, get whatever you want —product-oriented business—then ChatGPT is your godsend. Congratulations!

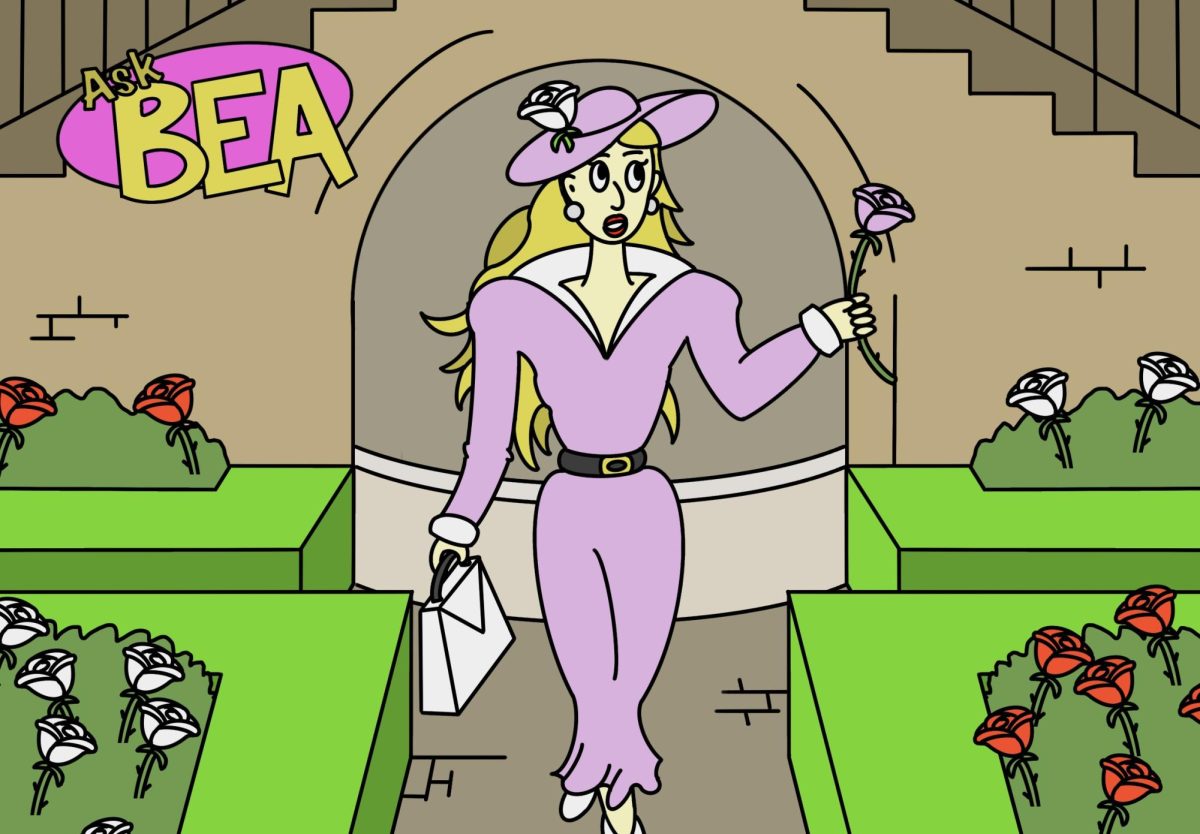

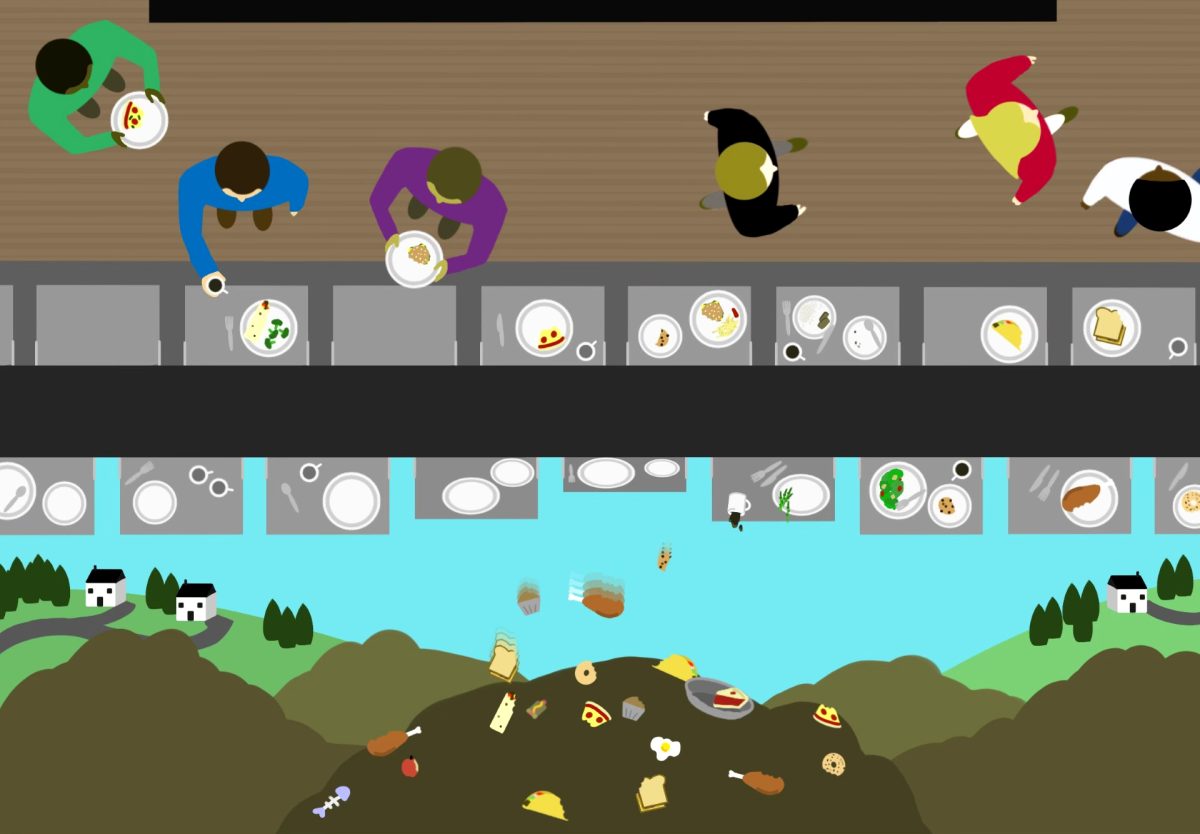

But if you are writing essays to learn how to 1) write and 2) think through a problem, you have no reason to use ChatGPT or even think about it. Writing is like an exercise we use to train our muscles. We enter a garden of ideation, arrangement, creation; we synthesize and argue in our papers – which is both beautiful and messy. We know how it feels to till our mind’s soil, to plant seeds of inspiration, to water blooming thoughts, to weed out distracting points, to harvest clear arguments, and lastly, to weave them into a masterful concoction of flavor for the academic dinner table. And while some creations will inevitably taste better than others, what I am getting at here is the process, not the product. With each writing process, we become more attuned thinkers, communicators and humans.

I am reminded of the new film M3gan, where a woman designs a humanoid AI bot (Megan) to cater to the needs of orphaned niece Cady and to protect her from harm. Megan gives Cady everything she wants in a strikingly similar way to ChatGPT. Megan surfs the web and learns to get better at her task— while Cady learns that friendship is a product. M3gan invites the audience to question the role of friendship which guides us to the same arena where we negotiate with ChatGPT. Are these AI products promising tools, or do they block us from energizing our built-in human tools that help us struggle?

If I let Megan or ChatGPT enter my life when they knock, they will head to my mind garden and scoff at me. They will gather all my tools—my tiller, pruner, rake, hoe, hose, gloves, and wheelbarrow— to then sell them for cheap and, with that money, buy me a Wendy’s 4-for-4 supper. I will be free from my labor, but my creation muscles will slowly rot away from neglect. And I might wonder why part of me feels missing while I eat the empty calories Megan served up.

“You’re not going to learn to be human by asking a machine what it means to be human,” said Dr. Hick. “I don’t assign essays so students can teach me philosophy. They don’t teach me anything. I do it because it’s a pedagogical tool—think by grappling with a problem and solving it.”

Replacing human struggle with AI has the potential to dehumanize us, to throw our physics out of alignment. If we understand education as a product, what will we learn? If we understand friends as props in a fantasy about ideal friendship, will we treat our friends like products? If we use our friends, professors, and mentors as products, how will we learn to use ourselves?

The Buddha once said, “it is better to travel well than to arrive.” As we grapple with seductive technology offering the promise of destination without any road to travel, this lesson reminds us of what becoming ourselves could mean. How could our relationship with struggle shift if we choose to turn a gentle cheek away from the need for perfection?

Megan doesn’t exist (yet) and ChatGPT added guards against cheating, but these bots do give us an entry point for dialogue about our values, product versus process. I invite you to examine how you approach struggle as you grow into yourself while at Furman, your mecca of learning and creation. What a human thing to do!