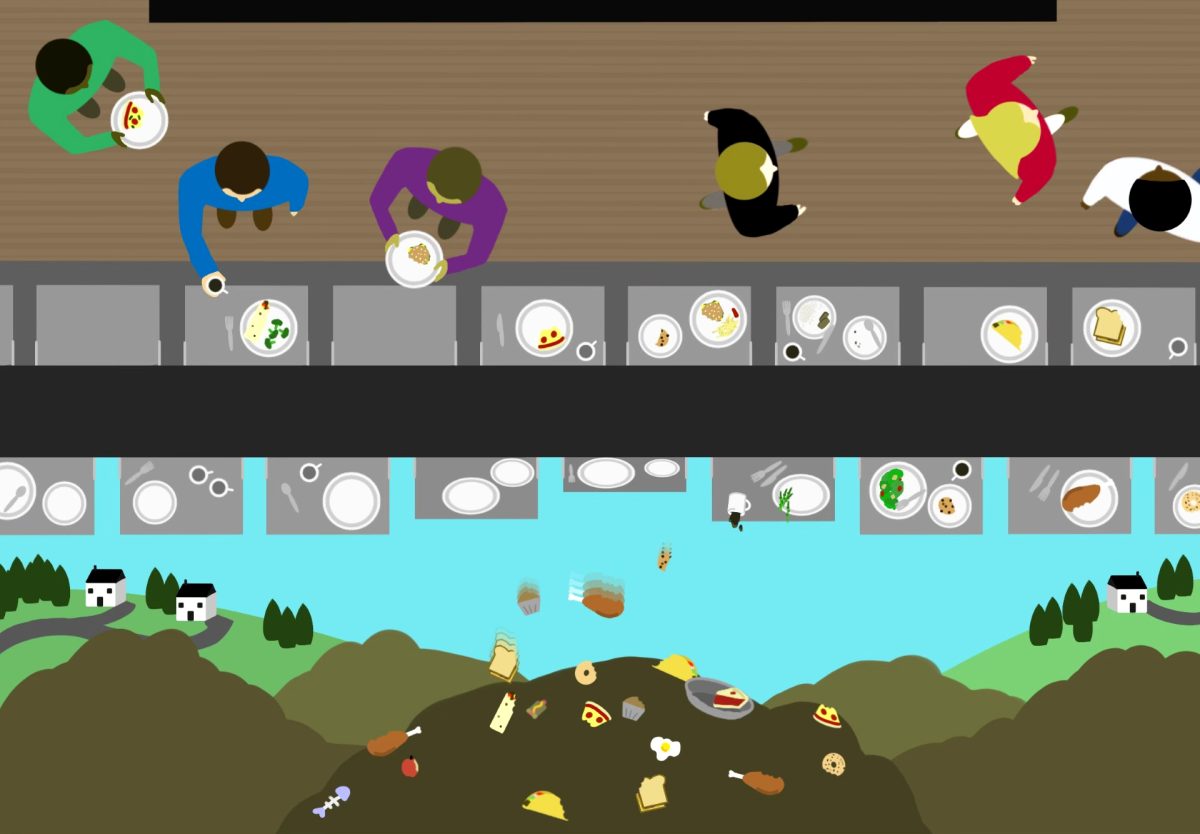

Food is perhaps the most basic of human needs. Prioritizing reliable access to safe and nutritious food is foundational to fostering an inclusive environment for every student to thrive at Furman University.

At the onset of the pandemic, food waste and food insecurity multiplied overnight as food and farming systems faced shocking disruptions in supply chains. Countless institutions with major food purchasing demands announced closures, causing industrial farms to destroy unsold produce, while grocery stores struggled to keep up with customer demand.

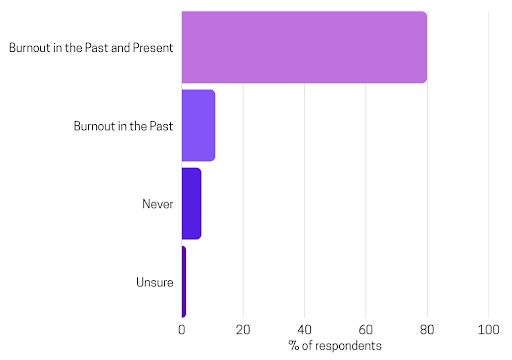

Resulting from the pandemic and subsequent economic crisis, researchers at Northwestern University estimated that U.S. household food insecurity doubled from 11.1 percent to 23 percent.

The experience of food insecurity is defined as uncertain or limited availability of safe and nutritionally adequate foods. It includes the ability to acquire such foods in a socially acceptable manner. The most extreme form is often accompanied with physiological sensations of hunger.

University campuses and students were not an exception to widespread insecurity. Even before the pandemic, college students have been consistently vulnerable to experiencing food insecurity. With the extreme cost of tuition, housing, and meal plans, not having reliable access to food threatens students’ ability to succeed academically and maintain their well-being. Food insecurity is particularly pressing for low-income students and those who lack access to government assistance programs.

According to the College and University Food Bank Alliance (CUFBA), 30 percent of college students experience food insecurity. This issue takes many forms and persists at all universities, burdening students across geographic locations, demographic statuses and enrollment levels.

The pandemic has only exacerbated these issues. According to a national study by Swipe Out Hunger and Chegg, nearly one-third of college students have missed a meal at least once a week since the beginning of the pandemic. Their research has suggested that more than half of all students sometimes miss meals and nearly half have experienced food insecurity.

Although food insecurity is more prevalent at public universities and community colleges, private universities are not exempt. Because 71 percent of Furman students come from families in the top 20 percent of the income distribution, it would be easy to think that food insecurity is nonexistent on our campus. This false perception leads to low-income students at Furman lacking resources compared to their peers at universities with a greater diversity of incomes.

But what might food insecurity look like on a campus like Furman? Consider this scenario:

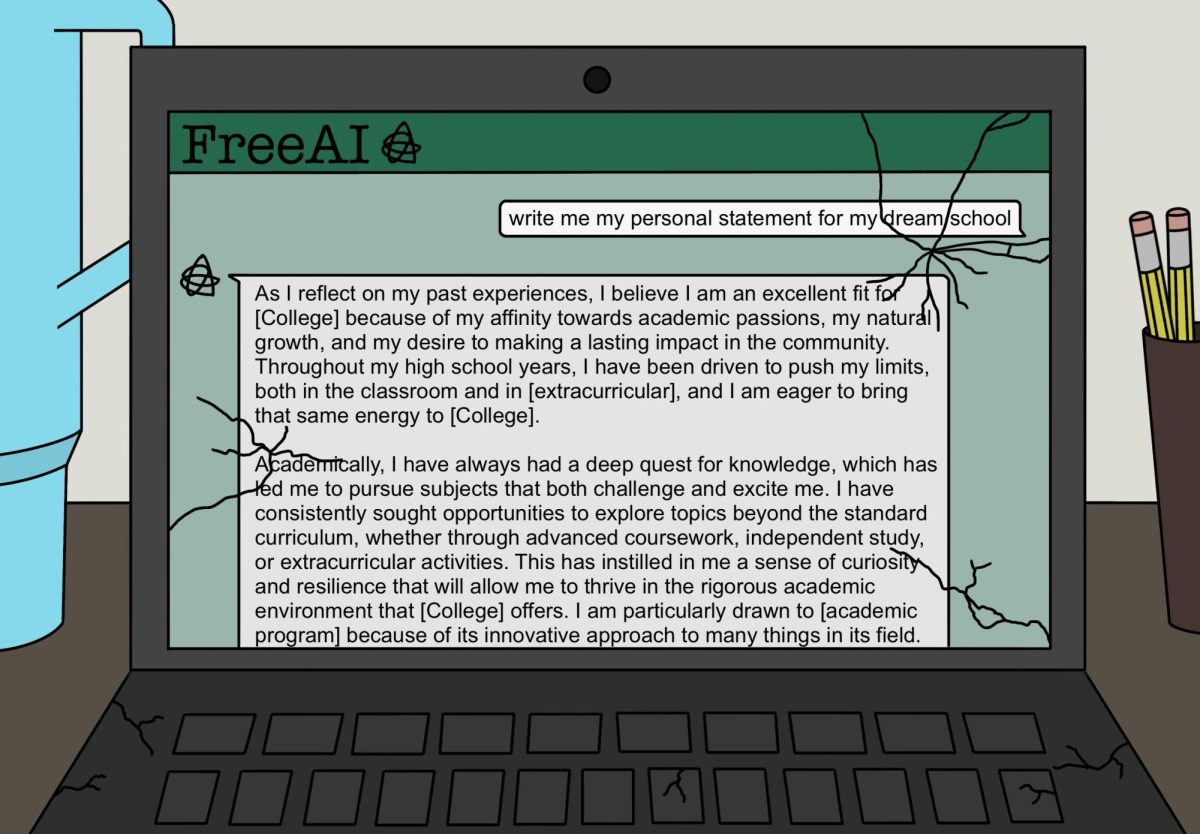

You finally reached the last week of exams. You have spent many late nights in the library studying, writing papers and preparing for presentations. You ran out of pala-points a week ago and have just a few swipes left. You have been skipping a meal or two every week to make them stretch. There are eight days remaining until the semester wraps up.

As simple and common as this sounds, this is an example of student food insecurity. And food-related stressors, stacked on top of hefty academic demands, no breaks, limited mental health resources and abrupt changes forced by COVID often result in an unbearable situation.

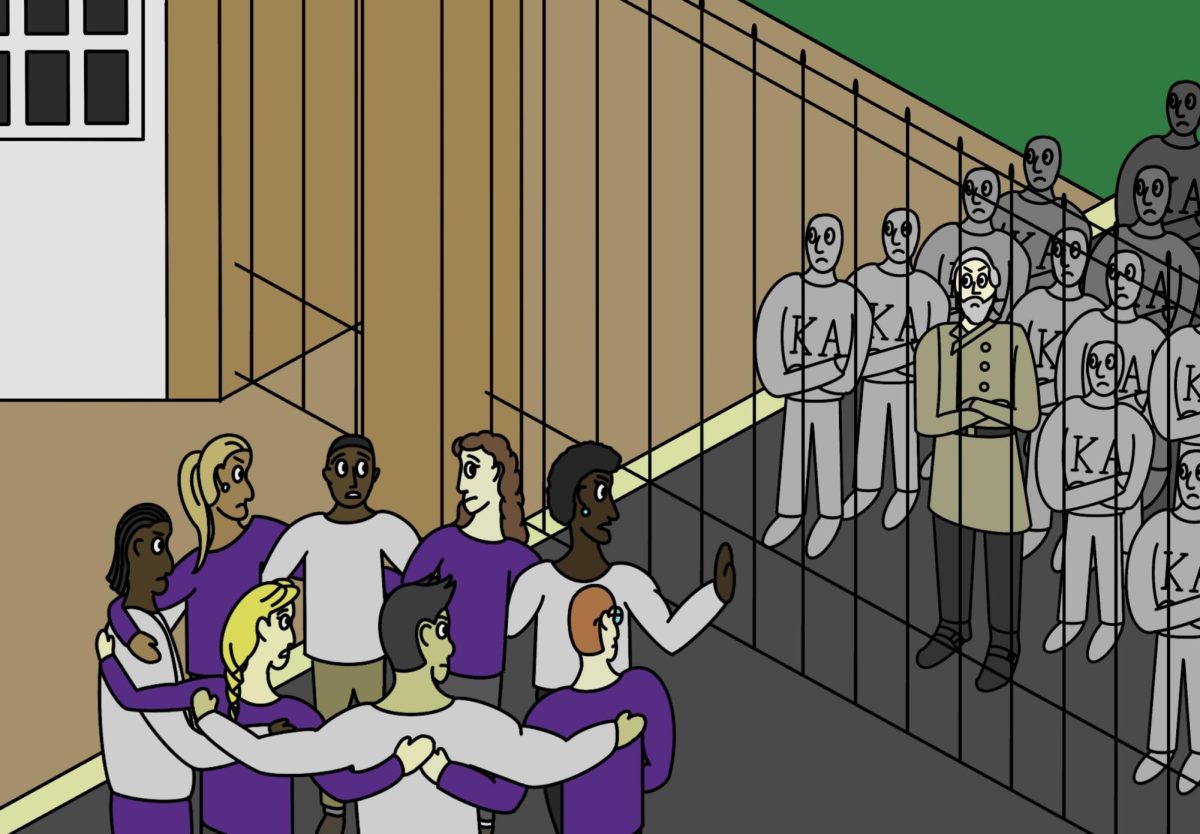

Still, students experiencing insecurity hesitate to assign their routine such a label. There is often a stigma attached to asking for help or even recognizing that habits such as skipping meals are unhealthy and problematic. At Furman, help is hard to find and potential programs to address food security have been met with resistance in the past.

This is unfortunate, especially because we know financial mobility for Furman students from low-income backgrounds into high-income statuses is rarely achieved. Therefore, supporting reliable access to food also means addressing economic segregation and equitable access to resources while enrolled.

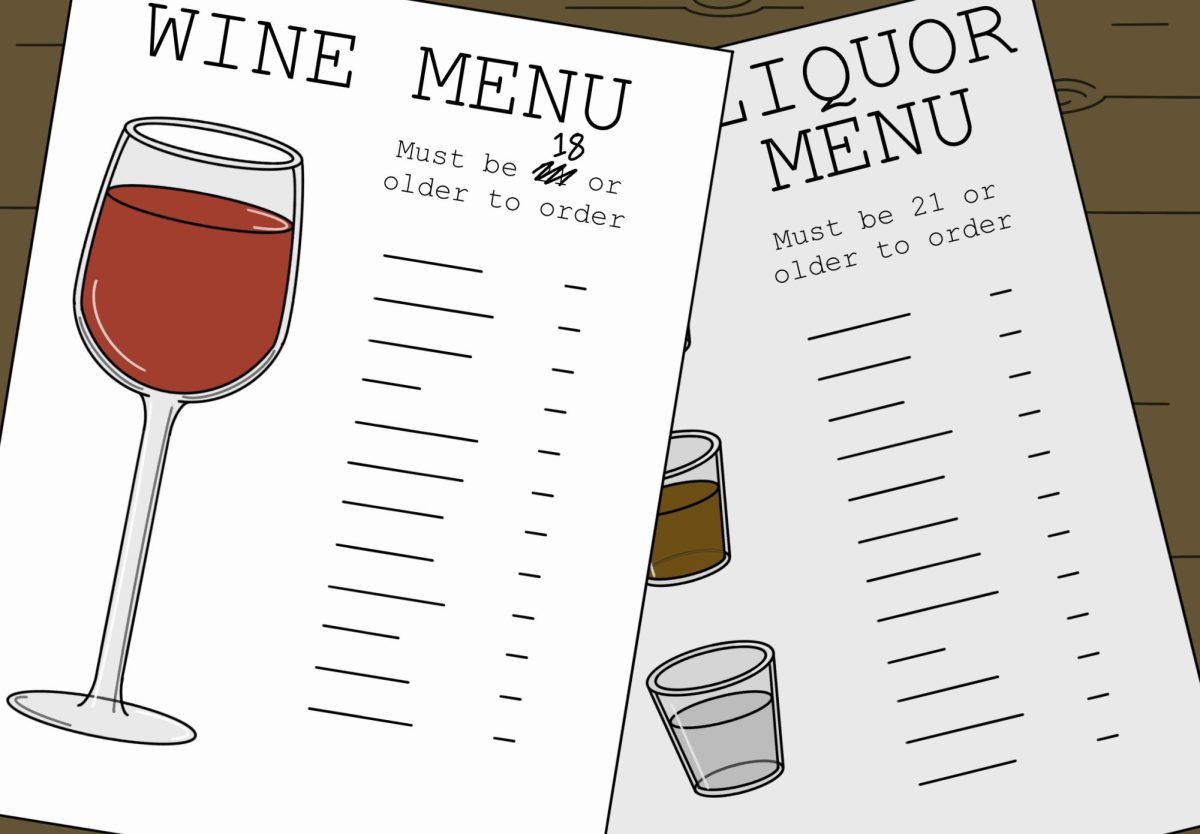

Swipe Out Hunger, however, has recently emerged as a promising program to address hunger on campus. This program would allow students to donate between one and three guest meal swipes to a “swipe bank” in which students facing food insecurity could apply to receive food swipes. The application process would maintain student confidentiality and only a small select internal committee would review applications. Swipes would subsequently be digitally added to a student’s meal card, maintaining privacy for each student that accesses this program.

On a national level, attention around this issue has been rising. Swipe Out Hunger is the original author and architect of the Hunger-Free Campus Bill, which passed in California in July 2017, and New Jersey in May 2019. When passed, the bill grants funds to public colleges to implement food security initiatives on campus, such as starting a meal swipe donation program, establishing food pantries, and creating SNAP enrollment opportunities. The legislation has proved effective at addressing student food access, and eight states have recently introduced the bill.

By introducing a program like Swipe Out Hunger, our community would better safeguard campus-wide food security and uplift students’ dignity. Furthermore, focusing attention to eliminate food insecurity on campus would signal that our Furman administration desires to support holistic physical, mental and emotional well-being alongside academic success.

Ramen noodles are not the answer. Being a “hungry college student” is not a rite of passage and despite housing, dining and workloads, college campuses are not always spaces of equal opportunity. We need student advocacy to pressure institutional action.

If you are interested in helping to bring Swipe Out Hunger to Furman, please reach out to Chloe Sandifer-stech (chloe.sandifer-stech@furman.edu) or Catherine Dawes (catherine.dawes@furman.edu).