The university has managed to avoid the crippling outbreaks many other institutions have fallen victim to, though not without strife. As of Nov. 3, only 88 students have tested positive since Aug. 12. That is a remarkable achievement given this fall’s shaky start and the administrations fickle approach to campus testing.

Yet now is not the time for a victory lap. There are still 3 weeks left in school, and as countless other universities have proved, cases can explode within days.

Vigilance is, of course, going to be the dominating theme in the upcoming weeks. But if the administration wants to end the semester on a high note, a change in policy is needed—with national case counts rise at a worrisome rate, complacency is as dangerous as the virus. Yet the change I am addressing is not one involving the student body. Rather, the adjustments needed now are regarding the most dangerous body of individuals on campus—faculty.

Total case counts on campus can be determined with a simple equation: positive students + positive faculty = total positive cases. Therefore, Furman’s containment strategy should address both parties. Yet the administrations testing policy only accounts for one of these factors, the students. Since Sept. 23, Furman has been adhering to the following strategy per a University email:

“At least 20% of the on-campus student population, including commuters and graduate students, will be tested weekly. Students will be selected for testing through random sampling, which could result in some students being tested multiple times, even back-to-back, throughout the semester.”

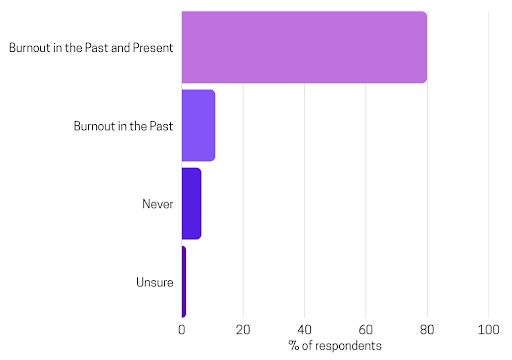

Faculty are only tested if they are deemed as “close contacts” with an individual who has returned a positive test. Therefore, as of Nov. 3, Furman’s COVID dashboard displays a mere ten faculty tested between Oct. 19 and Nov. 1, with three testing positive. In comparison, 894 students were tested, with nine tests returning positive.

It would be unfair to claim that the faculty had a 30% positivity rate. The circumstances for their testing differed from those of the students, making such a comparison illegitimate. Yet these rates prove that faculty are contracting the virus. They are not an immune party. In fact, they are the group most at risk to exposure.

Faculty are in constant interaction with the Greater Greenville Community. The very nature of their employment dictates they live off campus, which subsequently forces them to undergo a parade of to-and-fros that inevitably dictates contact with both Furman students and community members.

Furthermore, many Faculty have families or live in multi-person homes where co-habitants might attend Greenville schools or work in the surrounding area. So, while Furman Faculty might be careful to avoid the virus, it is naive to assume that they live in a vacuum and are at not a significant risk.

With nationwide COVID rates increasing, and Greenville County boasting a high cumulative incidence rate, the risk posed by faculty needs to be addressed by the administration. Right now, faculty are solely tested in reaction. If the pandemic has proven anything, it is that reactionary measures are already a step too late.

The administration should adopt the same random testing strategy currently applied to the students, meaning 20% of the faculty that teach in person should be tested weekly. It is difficult to imagine the faculty being apprehensive of this policy—more testing implies more safety and, considering the significant health risk many professors are taking by teaching in-person, increased testing seems like a courtesy more than anything.

Other campuses have already adopted rigorous testing standards for faculty. MIT, for example, tests faculty on campus four-plus days a week twice weekly. The University of Illinois has adopted a similar strategy, testing all faculty up to twice per-week regardless of days on campus.

If the administration wants to ensure the semester finishes successfully, they need to be aware of the risk posed by faculty. It seems reasonable to ask that the staff be held to the same testing standard as the student body. After all, as recent emails have fiercely promoted, we are a community. It is time testing protocols were reflective of that unified nature.