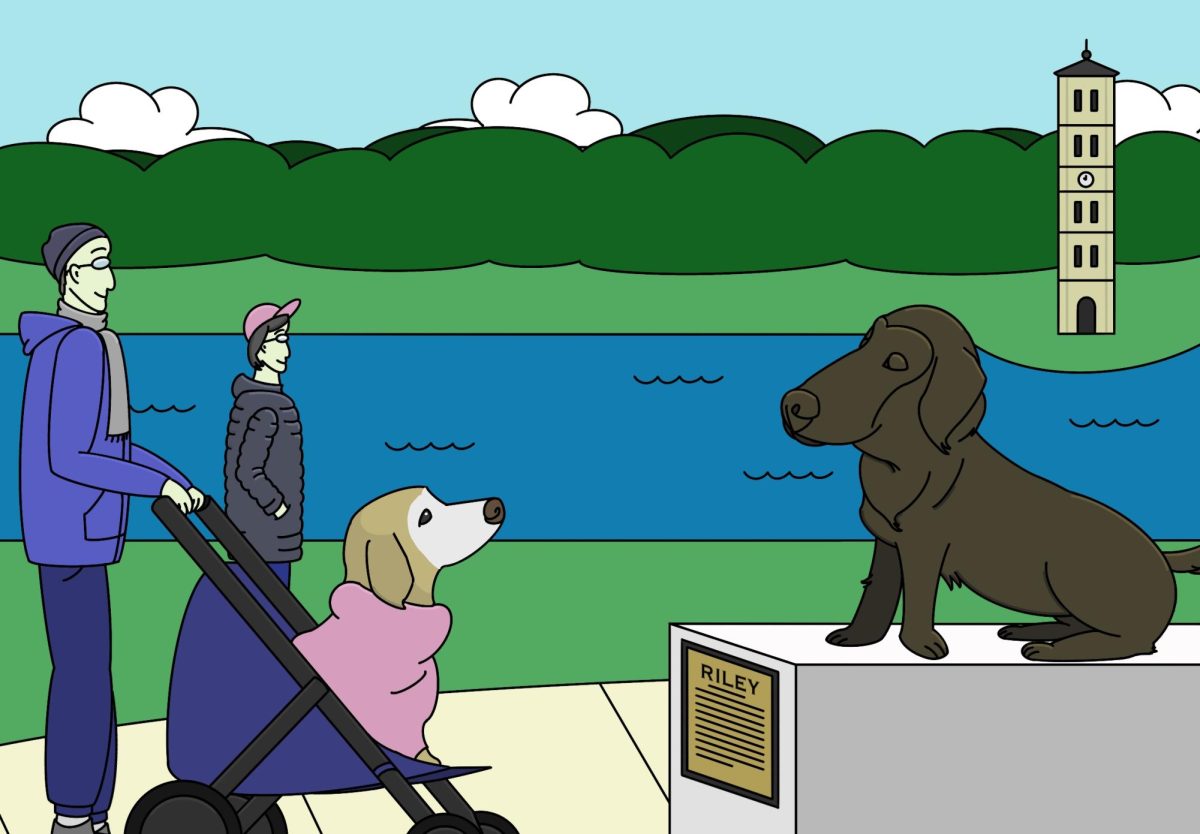

Wellness—perhaps one of the most used, and most misunderstood, blanket terms of the decade. It is an entire category of podcasts on Spotify, a buzz-word for boutique workout studios and exorbitantly priced juice bars, and the catch-all term plastered onto the title of the required Furman class, “HSC-101 Wellness Concepts.” The ambiguity of the term cannot be overstated. What one considers “well” could be entirely contradictory to the conception of another. For example, a certain student might think limiting themselves to a single dining hall cookie a day would be the epitome of health, while another might completely avoid the dessert bar on the regular. One might think a nine-mile run seems perfectly acceptable, while their peer consistently gripes about the walk from Furman Hall to South Housing. Basically, wellness is entirely personal…so how can Furman teach a class on it? Well, let’s backtrack. There are certain aspects of wellness that are universal. Getting 150 minutes of moderate exercise a week is generally recommended, as is eating a well-balanced diet of fruit and vegetables. Basically, doing things to ensure your health, i.e. your body and not it’s aesthetics, is functioning at a baseline level so you don’t kneel over while climbing the ever-steepening stairs of your dorm seems like an agreed upon goal. But what happens when this all gets extreme, and conceptions become skewed so that pursuit of wellness actually becomes unhealthy?

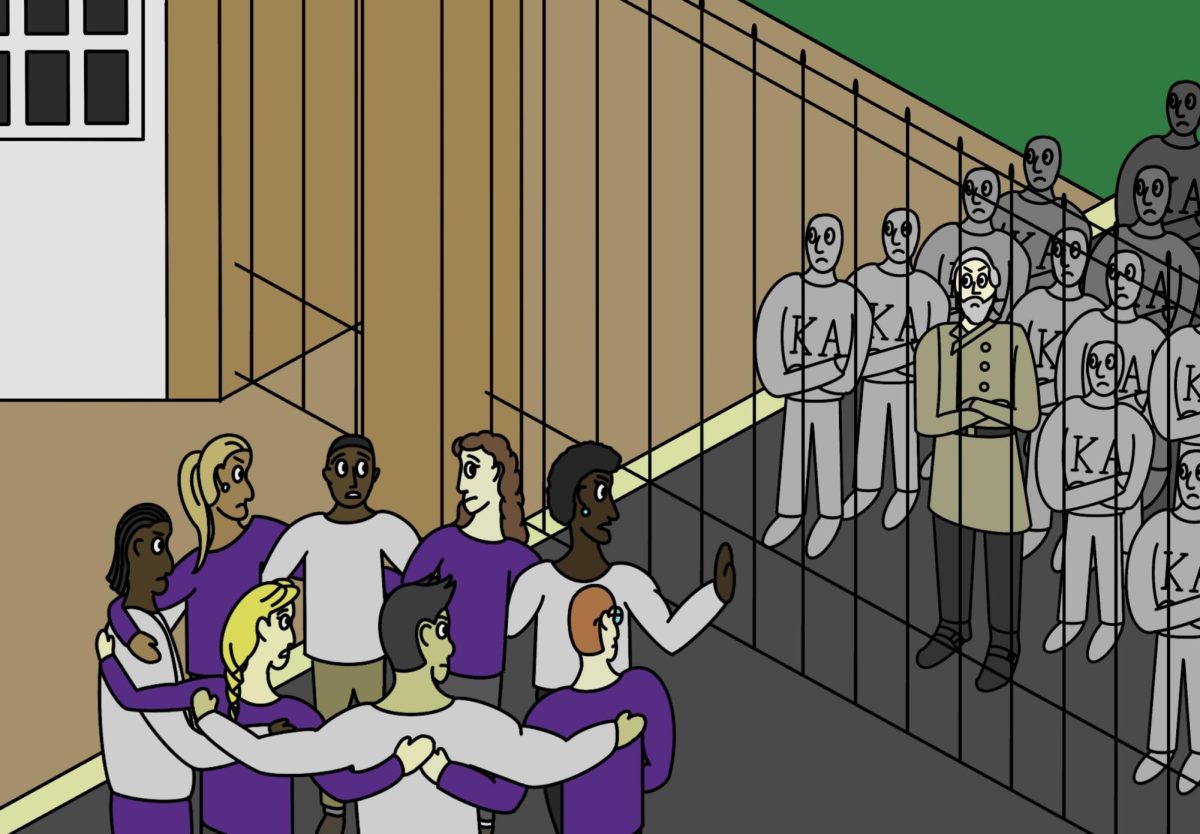

Let’s all acknowledge something—we live in a society hyper-focused on presentation, performance, and perfection. We also exist within the bubble of a college campus, where our insecurities seem to be put on stage for all of our classmates to see. We, whether you recognize it or not, live in a breeding ground for eating disorders. They come in all forms and affect a startling number of the population, often going unnoticed or unaddressed. While it’s usually a silent and personal battle, that doesn’t mean outside factors don’t influence the internal rhetoric of somebody struggling. Triggers, as they are often called, can be found everywhere. As somebody in “recovery” from a lengthy battle with an eating disorder, I see them everywhere—if you pay attention, I bet you would as well. You would see them in your friend when she complains about her thighs, or the girl in the dining hall on her low-carb, no-fruit, basically air-only diet. For me, sitting in HSC-101, I was confronted with an astounding number of these triggers— opinions and information I had been working to ignore for years. The controversy I was and am witnessing has lead me to question the validity of the course, and furthermore Furman’s right to require it for students.

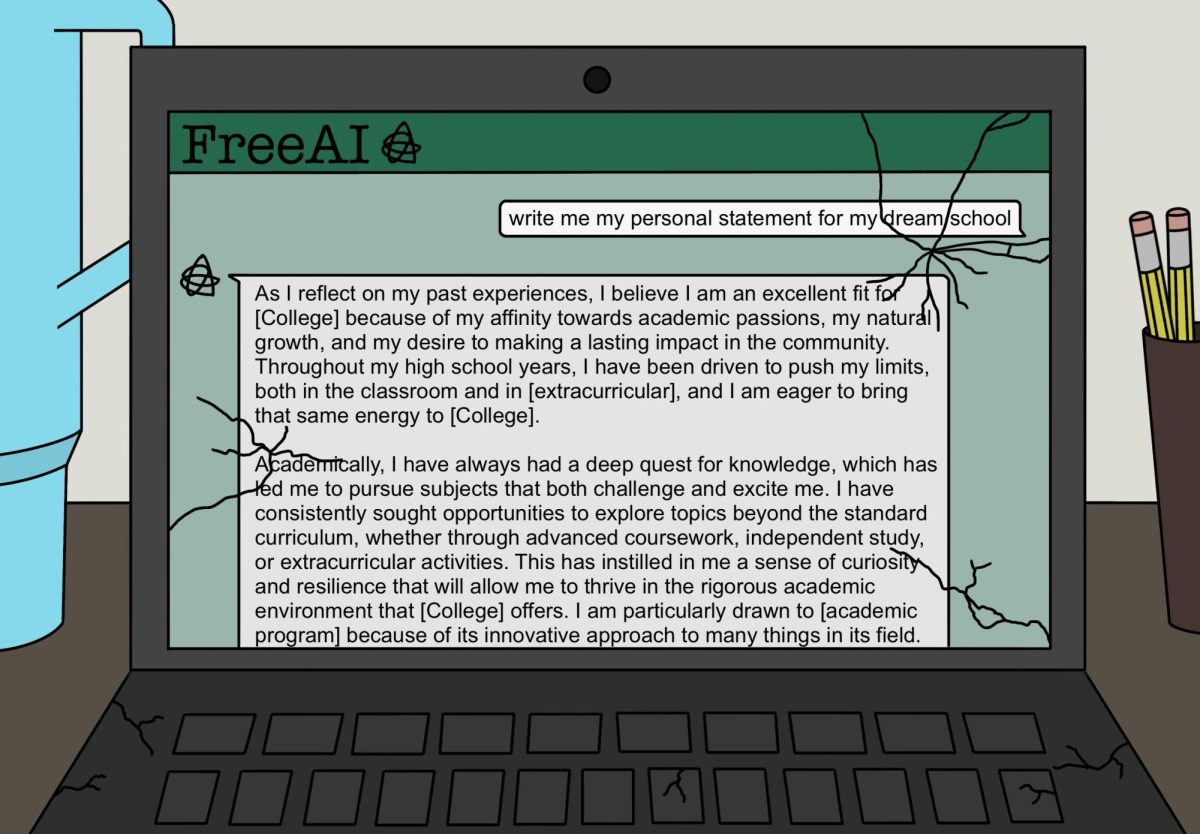

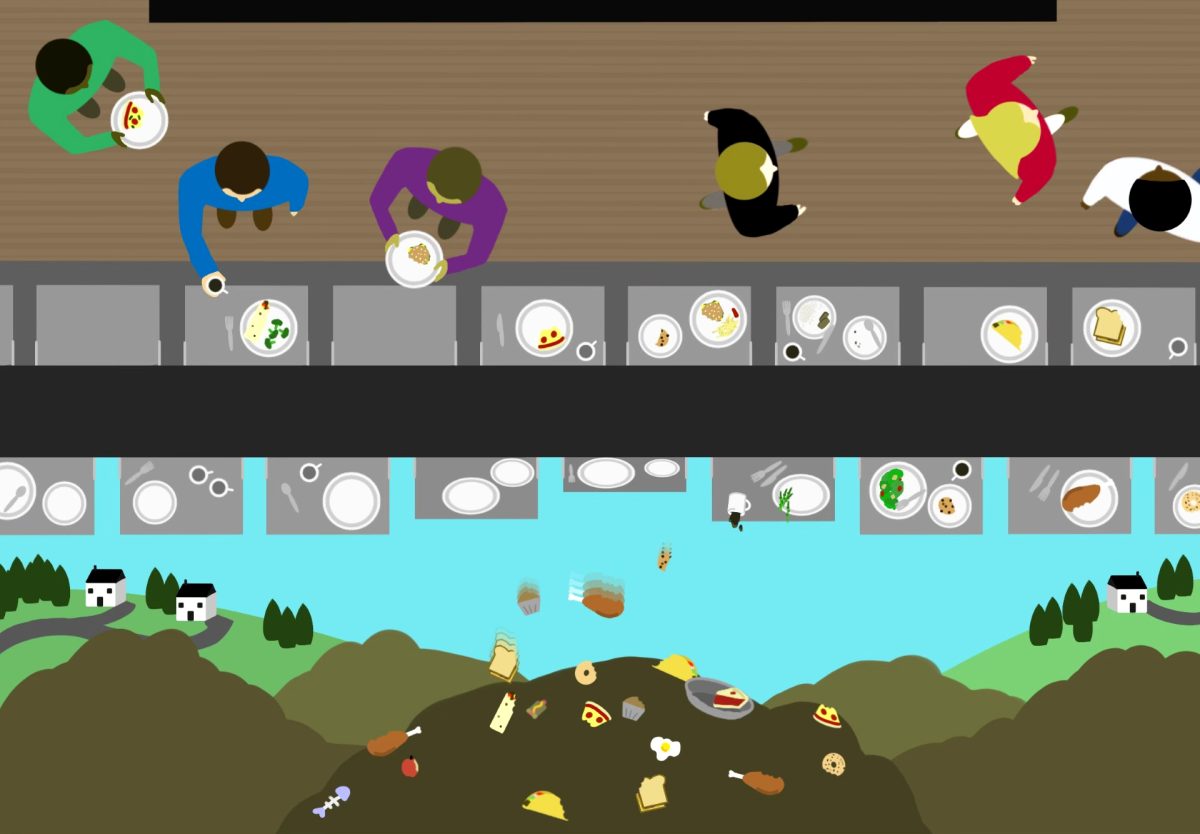

The slide pictures a piece of broccoli next to a muffin. My professor is snaking up and down the rows, asking students which option they would reach for in the dining hall. My eyes flicker to students shifting uncomfortably in their seats, unsure of what the correct answer is, or more accurately what the teacher wants to hear them say. Some, those braver than I, give an insinuated middle-finger to the questioner and proudly say the muffin. Others simply shrug. I just sit there and contemplate how wrong this entire situation is. Yes, we all know the broccoli is more “nutritious,” but as someone consistently trying to challenge the designation of “good” food vs. “bad” food, why is this man telling me that eating a muffin will send my health goals to die in a fiery inferno right next to the founders of McDonalds. Can’t we eat both? Isn’t diet an equation, a conversation not of black and white but of grey? You would think so, but never once has the word “balance” entered the conversation on diet or exercise. In fact, a lot of the information presented to us is polarized, promoting extremes in lieu of moderation. The textbook consistently emphasizes the benefits of longer workout, often over 90 minutes, and pushes intensity over enjoyment. Pleasure has actually been banished from the conversation, probably sent to go join Ray Kroc and that Cookout milkshake you enjoyed last night. No section proposes moving your body in a way you enjoy, but rather how to move your body to lose weight or “see” results. This appears a very archaic way of thinking, yet it is one being pushed onto every single student who walks across the commencement stage at Furman.

Honestly, I’m nit-picking here. My good-natured professor is not striving to negatively influence the 30 or so of us in the class—he’s simply perpetuating the societal constructs we have all been ingrained with. The ones that tell us washboard abs are the ultimate goal, that nothing tastes as good as skinny feels, that smaller=better. The lessons reinforced by magazines at the grocery store. You know, the ones at the checkout that glare at us with their glossy images of models on the cover, the ones that make us second-guess the Ben and Jerry’s in our baskets. This issue is much bigger than a wellness class at Furman, but on a campus that seems so focused on being “socially correct” how has a faux pas like this been ignored? Why did the dining hall have “healthy swap” cards next to various foods for a solid week, urging us to put back the cookie and reach for an apple instead, yet also put on a Halloween lunch bad enough to raise anybody’s cholesterol? What are the messages Furman is trying to convey? Yes, healthy living is something we should all strive for… but at some point harmless suggestion turns into a damaging mind game nobody wants to play.

In sum no, I’m not blaming Furman for giving us all eating disorders. I simply think the university and its professors need to be more cognizant of the opinions they are projecting given the precarious position young adults hold in the staggeringly-image focused world of today.