In 2017, The New York Times published an article titled “Some Colleges Have More Students from the Top 1 Percent than the Bottom 60.” The article presents a study by the Equality of Opportunity Project, which provides financial profiles for institutions across America, Furman included. When this study was published, The Paladin struggled to get substantial comments from Furman’s administration, and the article in progress was dropped. I want to address this study now, as a senior looking back on my time at Furman, because economic diversity is one of Furman’s biggest failures. It is a disservice to our student body and part of a larger system of economic injustice that we at Furman both endorse and ignore.

According to the study, the median family income of a student at Furman is $181,500, and 71 percent of our students come from the top 20 percent. Sixteen percent come from the top one percent. Furman is ranked number one in the South for highest median parent income and most students from the top one percent. We rank last in Southern colleges for students from the bottom fifth, and 2,345th out of 2,395 colleges nationwide.

Such campus demo-graphics make it easy to look around South Carolina and think Furman’s campus and downtown Greenville are normal, that the pawn shops and tire stores on Poinsett highway are an anomaly, that Sans Souci and the Corridor of Shame are exceptions. But the opposite is true. Furman is the exception, even if it cultivates an illusion to the contrary.

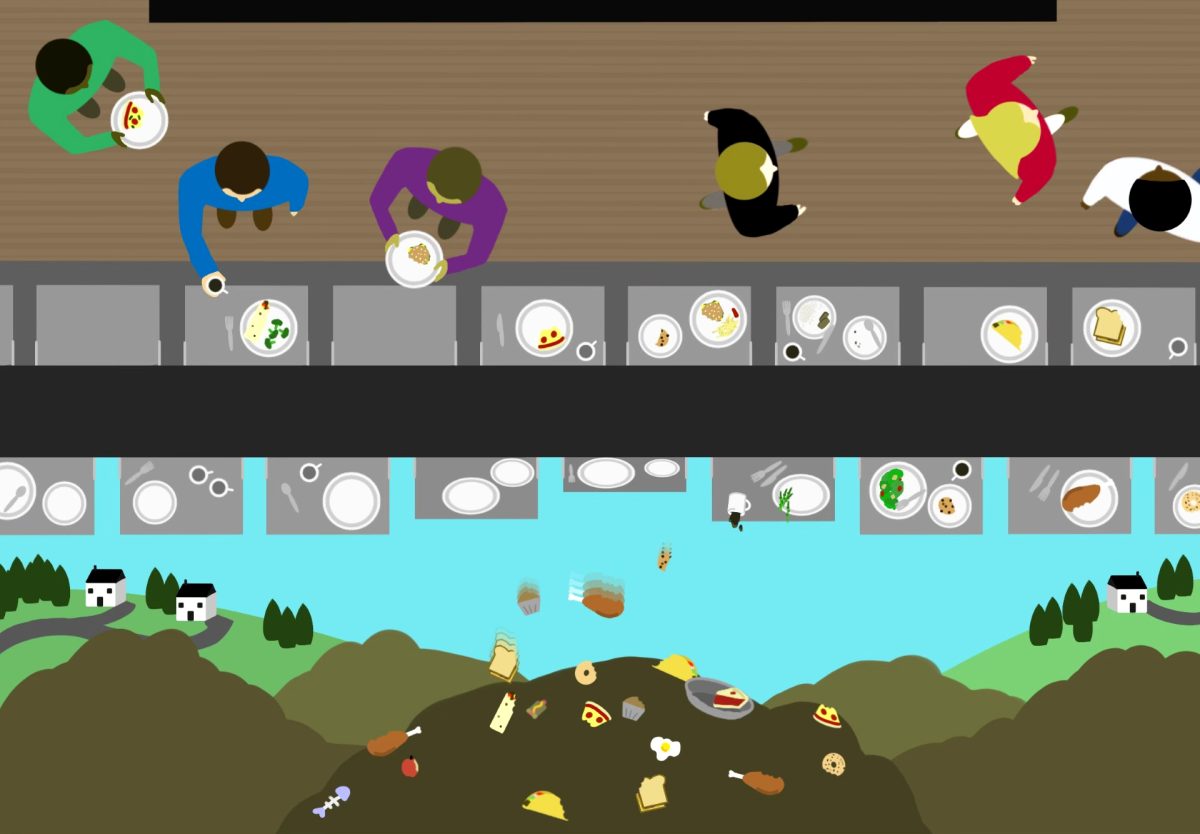

We do not have many students from the lower 80 percent, and those we do are certainly not from the bottom percentages. At Furman, most of us come from the top one percent and from the top 20. This is injurious to our students’ views of the world. Those in the upper ranges only have one another to compare themselves to, so when the majority of our student body — who come from the top 19 percent — compare themselves to the top one percent, they begin to think of themselves as less wealthy than they are; they start to see themselves as middle class. They lose the ability to recognize what wealth really looks like.

Some of us probably do not even know that a family income of $180,000 puts you in the top 20 percent. Not worrying about your financial stability, having healthcare, the freedom to travel and the resources to attend college — all of that makes you wealthy. Most “middle class” people at Furman are deeply not middle class. They’ve been conditioned to see themselves that way, and in doing so, they raise the bar of what they think poverty looks like. They overlook the horrible reality of economic injustice because we are living and learning in an environment that encourages us not to see it.

Furman’s economic homogeneity incubates a particular view of the world. We normalize wealth to such an extent that we fail to fully recognize it as wealth. We forget that the wealth of our student body is abnormal, that campus staff are living more economically “normal” lives than 75 percent of our students. We think of poverty as something you encounter as homelessness or on mission trips. But poverty is not “over there.” Poverty is American. Poverty is common and universal. It is oppressive, racist, disempowering, and violent. It is about lacking the resources to meet minimal living conditions and opportunities. Poverty makes a lie out of the American Dream, which so many Furman students can afford to believe in because they have never fully understood the lived experience of those who are not born into that dream already achieved.

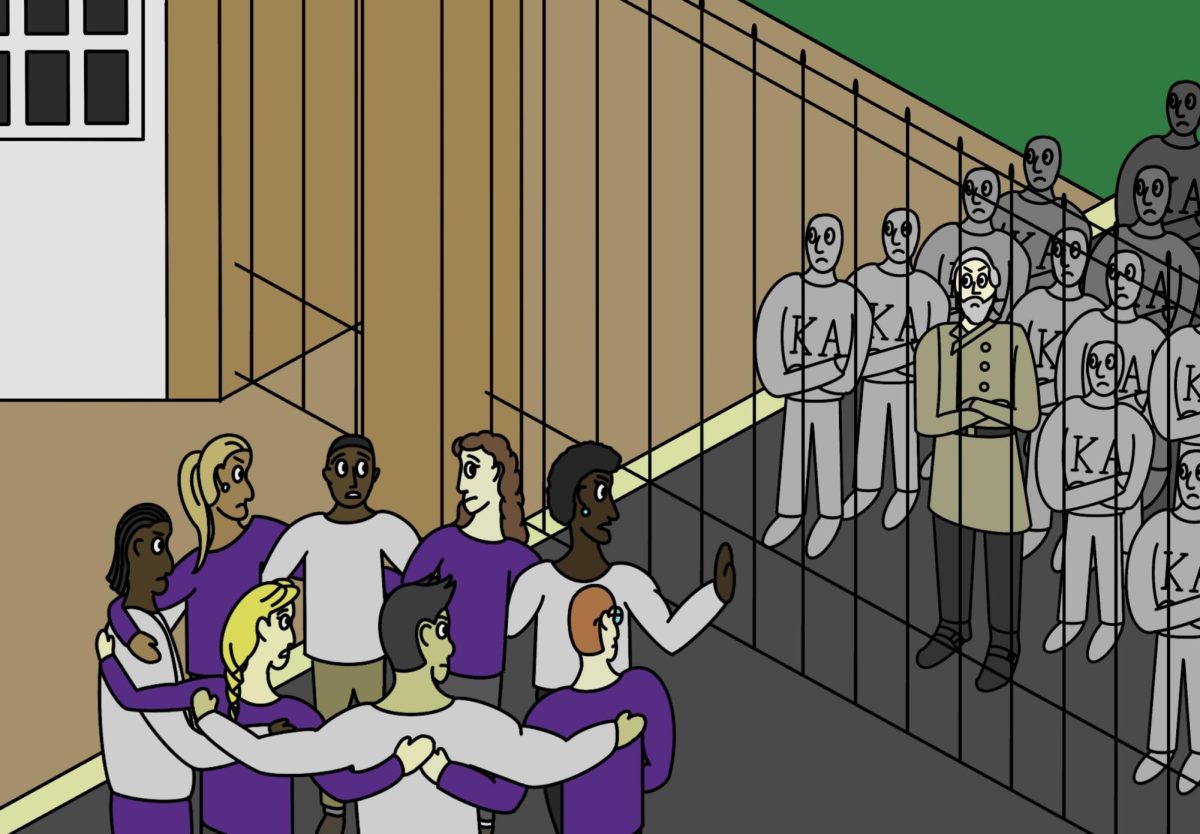

Many of our students are living in an artificial world co-constructed by Furman and by their own privilege, a world made of fountains, hedges and ivory towers. Our university’s 63.5 percent acceptance rate is not about academic standards, it is about wealth — though many of us are reluctant to own that truth.

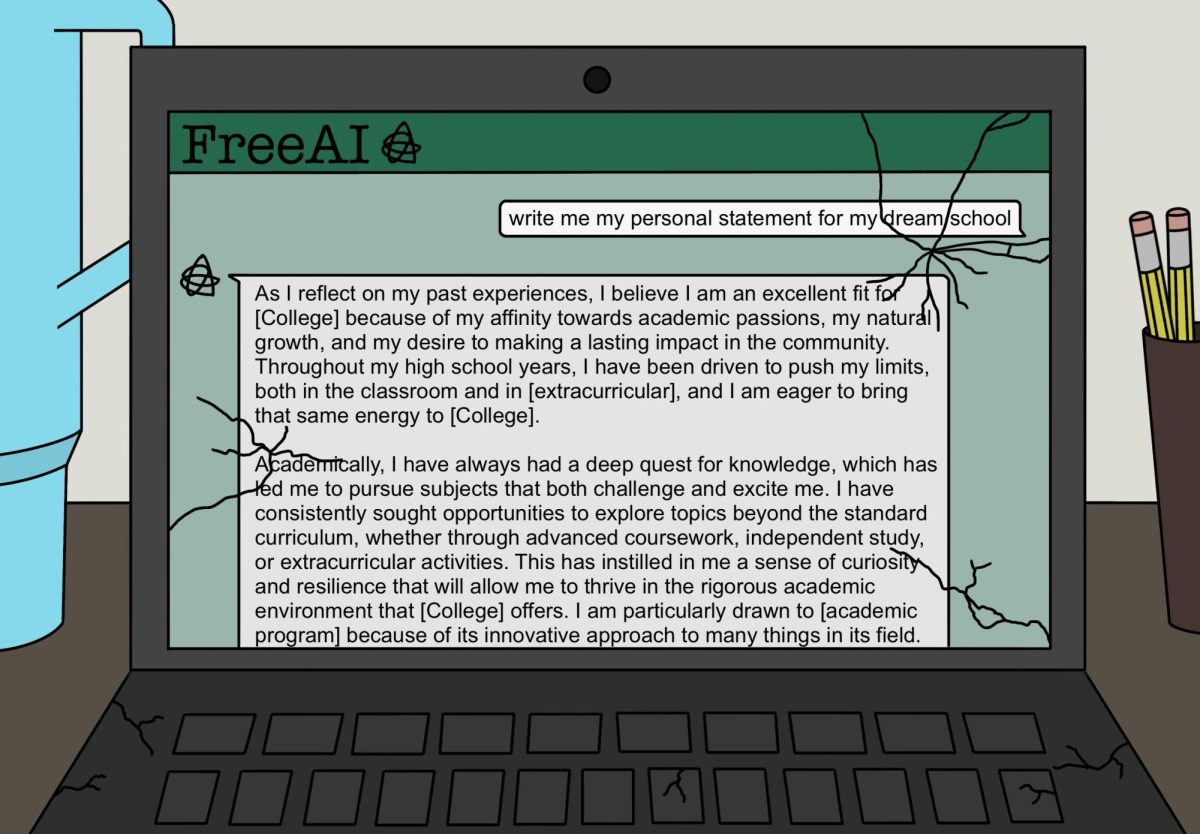

The problem with wealth at Furman is that we incubate privilege and dispassion, then send our students out into the world to perpetuate the same systems of wealth and privilege that brought many of us here. It is a failure to educate. As a result, many of us are either politically misguided or politically complacent, and our connections often place us in positions of power that have real world consequences for the people we have been conditioned to ignore.

The ignorance on our campus is shocking to those who know better, but there are not enough of these people to treat the problem. We desperately need an economically diverse student body so that this is not the case.

Speaking as one of these students, I am tired. I am tired of working five jobs to pay off my debt, and I am tired of Furman breeding ignorance. Poverty, for many of you here, is a mythic, exaggerated thing that exists in a reality very far from your own. Furman is partly responsible for this. Enrollment should not prioritize the Furman brand over the education of our students, and our students should not seek out that brand as a safety net for backwards ideas about the world. We are here to learn. Both Furman’s administration and our student body need to do better. We need to change our student demographics and look beyond campus at the world outside hedges, fountains, and ivory towers.