In 2014, the Greenville News reported that a master plan for the trajectory of public art was underway. A follow-up from art representatives and gallery curators in the area signals progress. Despite some standstills in the design process, art is effectively being catapulted into a realm of the never-before-seen in the Upstate.

From Greenville’s rooftops, the birds-eye-view reveals the scope of the city’s developing art scene.

A public walking tour along Main Street streamlines 63 sculptures for viewers to visit. Some of the works align with the vision of the Arts in Public Places Commission, a cohort of nine volunteers from various backgrounds who seek to push public art into a new era; while a shadow of historical preservation nostalgically keeps the statues of white male figures standing tall.

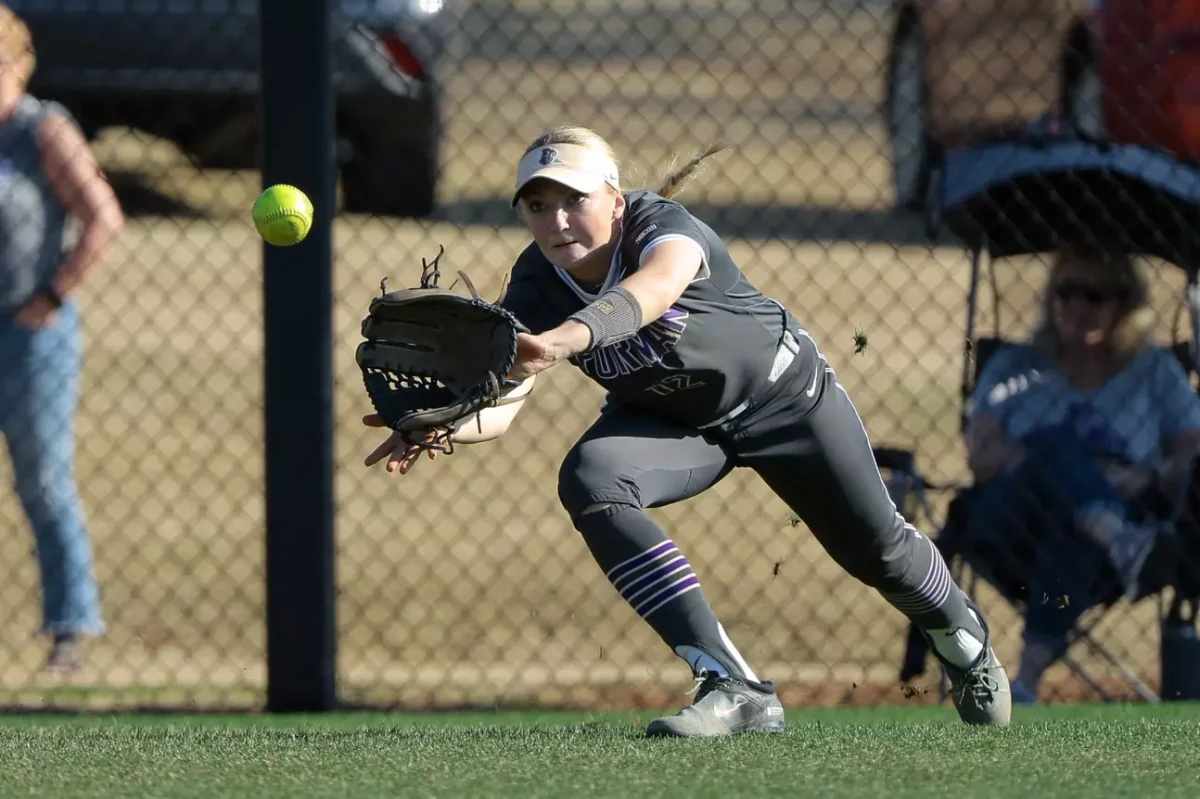

Curators are upping their criteria for selection. Among the few, Art Program Specialist Marta Lanier is apart of a special faculty at Furman University. Their opinion helps decide which artists to showcase in the Roe Art Building on campus.

Lanier insists on the priority that the artists bring a sophisticated resume and a good technique to the table. The faculty receives proposals for wall space in the Thompson Gallery, and then evaluates the educational benefits to the students. “It’s about the medium and the talent of the artist,” Lanier said.

‘They get to interact with the community’

For the final exposition of the Fall 2017 season, the Furman art faculty invited two-dimensional artist Nishiki Sugawara-Beda to expose her painting series HANA. She is a Japanese immigrant who paints linguistic compositions on watercolor paper. To Sugawara-Beda, the Japanese craft of calligraphy “is a dance, frozen in time.”

Lanier praises her multidimensional use of materials.

Before curating the gallery for HANA, Lanier considered the floorplan for the series. Sometimes artists arrive with an idea already in mind for how they want to design the gallery, but Lanier coordinated the installation of Sugawara-Beda’s paintings on her own. On the far-left corner, she motions to three out-of-order titles. The design creates a bleeding effect and a feminine harmony between the paintings, Lanier explained.

The task in the curation process is to not only to construct the artist’s’ vision, but to peek student attention from outside the gallery. Gaining foot traction is important given the tucked away, relative slightness of Furman’s exposition room.

Typically, Lanier and her colleagues do not host local artists back-to-back, although this year was an exception with Greenville native Elaine Quave and Furman alumnae Sali Christenson earlier in the season. The faculty tends to accept artists from outside the area, pushing the reach of student exposure to diverse limits.

Furman’s art department is partners with the Arts in Public Places Commission (APPC). Each May, a mural class called “Art and Community Engagement” is offered. So far, students have already painted walls in Travelers Rest and on Stone Avenue. “[They] enjoy it because they get to interact with community,” Lanier said.

But in terms of the larger art operation downtown, the artists working with Furman are issued a small stipend compared to the APPC’s $75,000 annual budget.

The commission is appointed by the mayor and is comprised of local architects, muralists, interior designers and gallery owners like Lindsay McPhail. Located on Main Street in downtown Greenville, The Art Cellar is an eclectic collection of 60 artists from all mediums, as well as a work studio for four resident studio artists.

McPhail discussed the spacing issues she experienced at The Art Cellar’s former location underneath the Bellacino’s on S. Main Street. Now that she is settled into her underground hideaway across the street from The Artists Guild Gallery of Greenville, McPhail oversees her space with business-like authority. She is looking for artists “who [are] doing something we don’t already have.”

Incidentally, McPhail’s selection process echos the one Furman’s art faculty goes through. At The Art Cellar, prospective artists upload their portfolio, submit questions and images on an online application. The waitlist for wall space in McPhail’s art wonderland can run up to eight months at a time. Though the pieces in her gallery are rotated, some of the artists have been apart of McPhail’s collection for six years.

Outside of her duties at The Art Cellar, McPhail meets monthly with her fellow APPC members to review art proposals from private commissioners. Once the team “gives their stamp of approval,” McPhail said, the APPC’s recommendation is turned over to city council, and it is up to them at that point to decide whether or not a public art piece is commissioned.

The APPC is a middleman for public art curation in Greenville.

But this year, the APPC finally received headway to recommend their own piece for addition to the sculpture scene downtown. Tracy Ramseur, Development Coordinator for APPC, relayed exclusive information over a phone call about the city’s upcoming installation, Kwilt .

According to Ramseur, the APPC toyed with a modern conceptualization of the plaza where the bronze Shoeless Joe Jackson statue formerly stood. It is in honor of Chicago Red Sox player and Pickens county native Joseph Jefferson Jackson. The decision came with “a general interest in diversifying the collection,” Ramseur added.

Ramseur’s goal to fill the void in the downtown plaza by the summer of 2018 is hopeful, she suggests, but the APPC is waiting on city council’s approval to redesign the space to better accommodate the size of Kwilt .

To be continued on Feb. 8