There have been few international agreements that have incited as much controversy as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), more commonly known as the Iran Deal. From its very inception, the plan was met with fierce hostility from many quarters of American politics. Now, as the President looks to nullify it, he has been met with more hostility. It seems that no matter what happens in Washington, no one is happy with this agreement, and there is a reason why. The reality is that neither side of the initial debate are wrong.

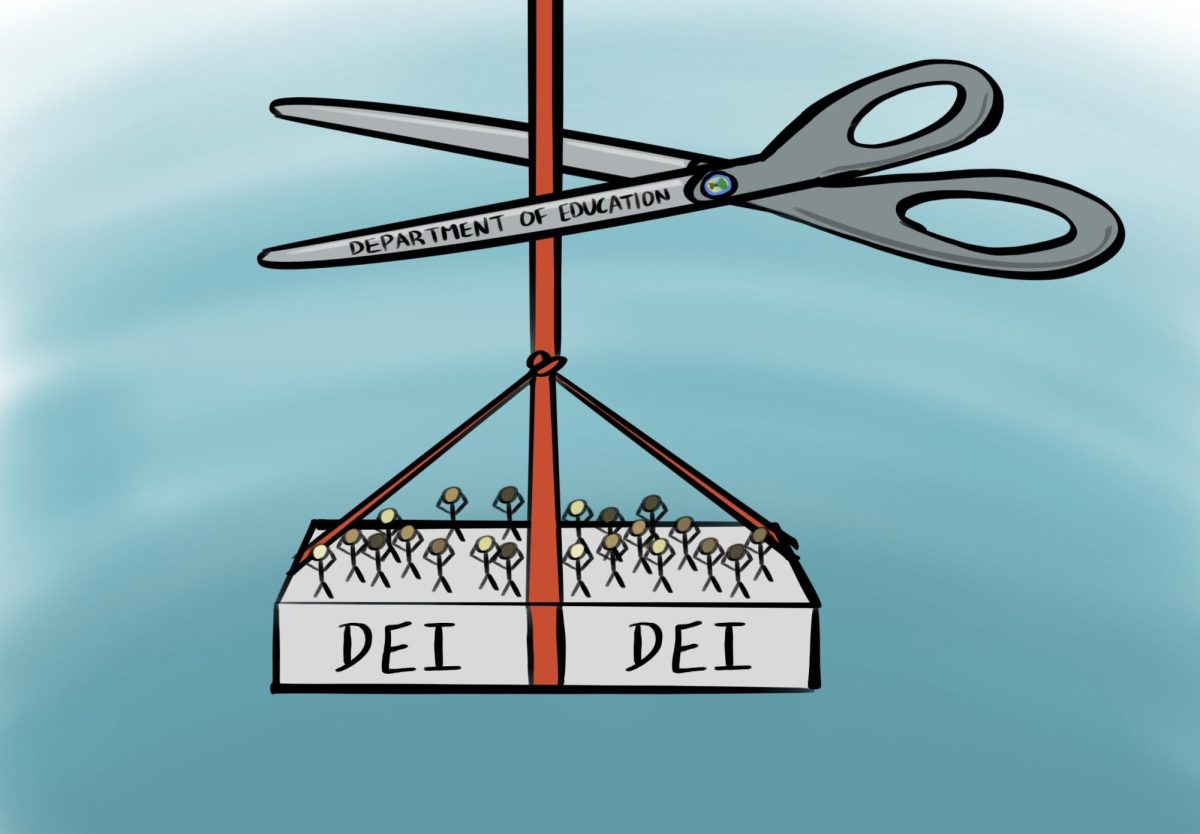

The Iran Deal is not a good deal, and it has yet to improve. However, disregarding it would cost America a great deal of international legitimacy and take away our already limited ability to keep tabs on Iran’s progress towards a nuclear weapon. The deal was a bad one, but now that it has been made, removing it would be akin to cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face.

The reason for all the controversy around this deal is simple. Americans tend to be passionate idealists in foreign policy. Particularly since the end of the Cold War, Americans have perceived every technological advance, every third world revolt, and every major event as another step on the path towards to the spread of our form of liberal democracy across the world. Think of it as a 21st century manifest destiny, an idea that history is marching forwards, drawing the world ever closer to our ideals.

This impacted American thinking leading into the Iran deal. Many in Washington and across the country thought that their willingness to negotiate meant that they had given in to our way of thinking, that this was their first step on the road to becoming a true liberal democracy. This was not the case. Iran began negotiating because it was in their interests to do so. Their economy was suffering, and they needed something to keep their people from questioning them. Therefore, they were willing to work with the international community in order to lessen the sanctions placed on them.

The Iranian government knew that in the end they would still be able to get nuclear weapons, and the minor delays that the deal imposed on them would be worth the influx of cash that would follow. The Iranian government has acted this way before. In 2003, they allowed the United States to use their airspace for missile strikes on Iraqi targets. Again, they did not do this because they sympathized with the United States; they did it because the destruction of the Saddam regime was in their interests. Saddam ran a Sunni regime in a majority Shi’ite State. Iran is a Shi’ite state, and so its government was directly opposed to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Iraq was consistently a balancing force against their influence, and this was most evident during the 8 years of the Iran-Iraq War. Now that Saddam’s regime is gone, Shi’ite groups sponsored by Iran have attempted to control the country. Ultimately, Iranian officials cooperated with the United States to bring down Saddam Hussein not because they wanted to work with America, but because they felt it would help them alter the balance of power in the Middle East.

The lesson Americans must take from this episode in our history is that we must not confuse our ideals with our strategic priorities. The Iran Deal is just the latest in a long series of strategic mistakes stemming from this pattern. Given an increasingly multipolar world, focusing on a dogmatic view of progress will inevitably lead to more mistakes. With this future in mind, the United States can and must decide on policy guided by a principled realism, one that will better protect not only our citizens, but the citizens of the world as well.