What are the best economic policies for a society, and how does income inequality relate to “good” society? Once a plan is decided upon, how do we get people motivated to create legitimate political action?

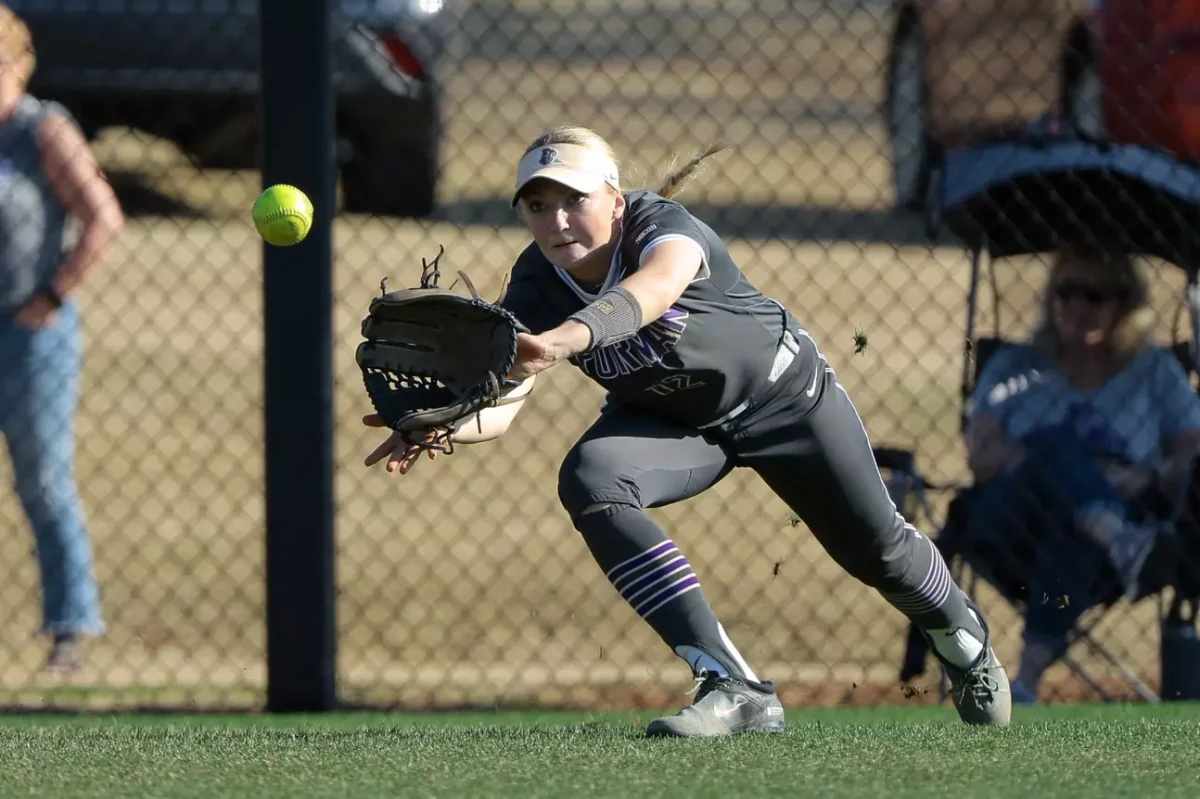

These, and more, are the questions that the Furman College Democrats hope to inspire in the Furman student body. The group recently held a Cultural Life Program event in Burgiss Theater that played the 2013 documentary “Inequality for All” in an attempt to stir inquisitiveness and action into the student body.

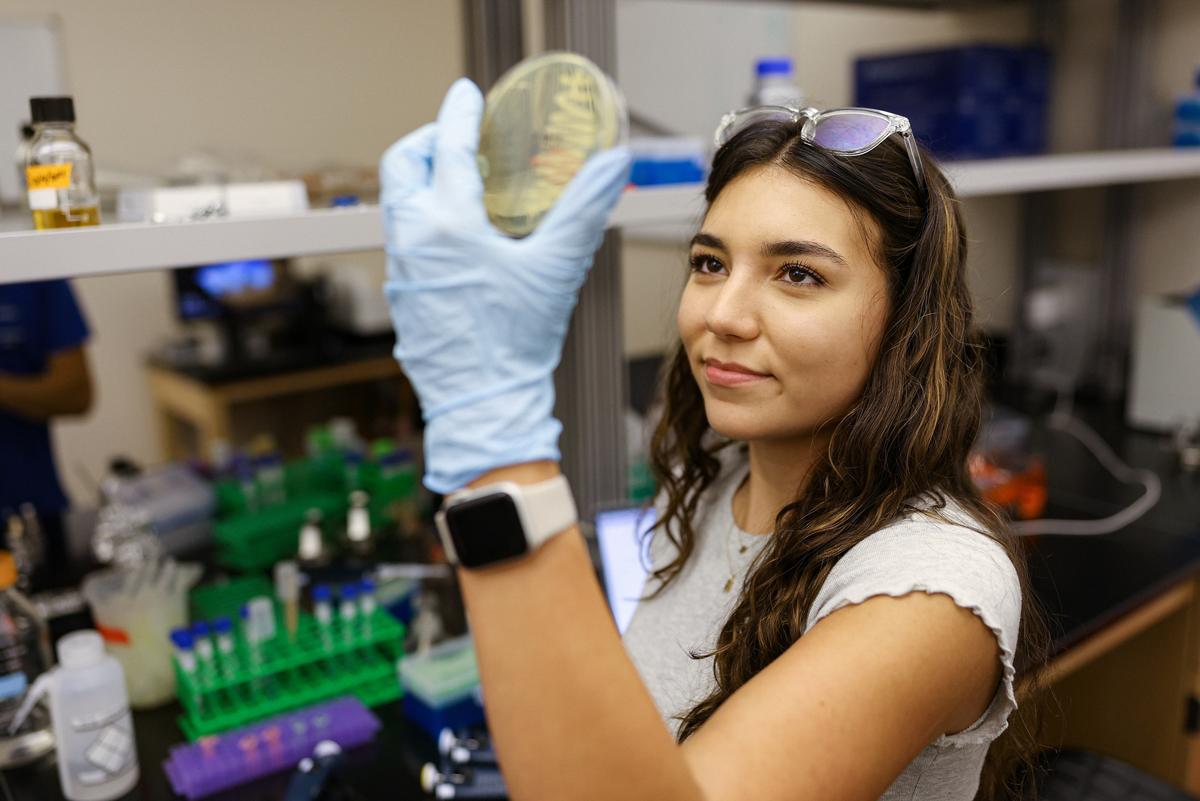

Sarah Cook, secretary of Furman College Democrats, aims to “mobilize, organize, and energize” the student body with her presentation of the documentary.

The movie, directed by Jacob Kornbluth, followed the former Secretary of Labor during the Clinton administration, Robert Reich, as he traveled around the country, explaining his views on the economy. It paired the stories of struggling Americans with animated graphs, a combination that highlighted both the personal and economic atrocities associated with rising income inequality.

Both Republicans and Democrats can agree that income disparity is a real problem in the United States. Liberal Democrats, like Secretary Reich and the creators of the documentary, however, differ from their political counterparts in their approach to this problem.

Reich argues for a common-sense economic policy based on government subsidies for the middle class instead of the upper class. His initiatives and reforms attempt to strengthen the middle class.

Current law allows for huge subsidies and tax breaks for the richest Americans. This “trickle down” policy is justified by the idea that the wealthiest Americans will use this money to create jobs and improve standards in the industries they own.

Billionaires like Warren Buffet and Nick Hanauer are quick to point out in “Inequality for All,” however, that the bulk of this money is not invested in the general American populous, but rather finds its way into the pockets of the top one percent of Americans.

When considering the documentary this side of the aisle, it appeared that the film included at least one logical disparity.

The first scenes showed an iconic graph measuring income disparity in the United States by year. It showed the top richest percent of Americans’ share of total national wealth since 1913—the year the census began. This graph eerily resembled a suspension bridge. One of the two highest points is right now, the United States in the year 2014. The other highest point was in the late 1920s, just moments before the Great Depression.

Secretary Reich did not hesitate to point out this correlation—the main theme of the documentary. Time and time again he compared the timeline of income inequality to American phenomena like wage flattening, personal debt, and inhumane work hours. However true Reich’s claims about the nature of a society in which not everyone has the same amount of money may be, “Inequality for All” failed to show a concrete correlation between rising income inequality and a fall in American economic supremacy. This led some CLP attendees to question some of the documentary’s conclusions about income inequality.

“Inequality for All” highlighted students’ need for political activism and thought.

For College Democrats President Mallory Taylor, “The first step to mobilization is recognizing that…issue that you’re really passionate about.”

Experiencing movies like “Inequality for All” can be that first step towards political action by a powerful bloc of voters—the collegiate student body.