At first glance, The Ides of March looks like another one of those plays-turned-films that will come to the Academy Awards, pick up an Oscar or two, be nominated for a few more, and then be swept into film trivia history.

In spite of its already questionable legacy, there’s a great deal to be learned from the film.

Somewhere behind the cast (which is alternately sexy and talented), the lazy screenplay, and a few thematic references to The Godfather, patriarchy looms. The constructed binaries of masculinity/femininity are as deeply embedded in the film as they are in our collective consciousness.

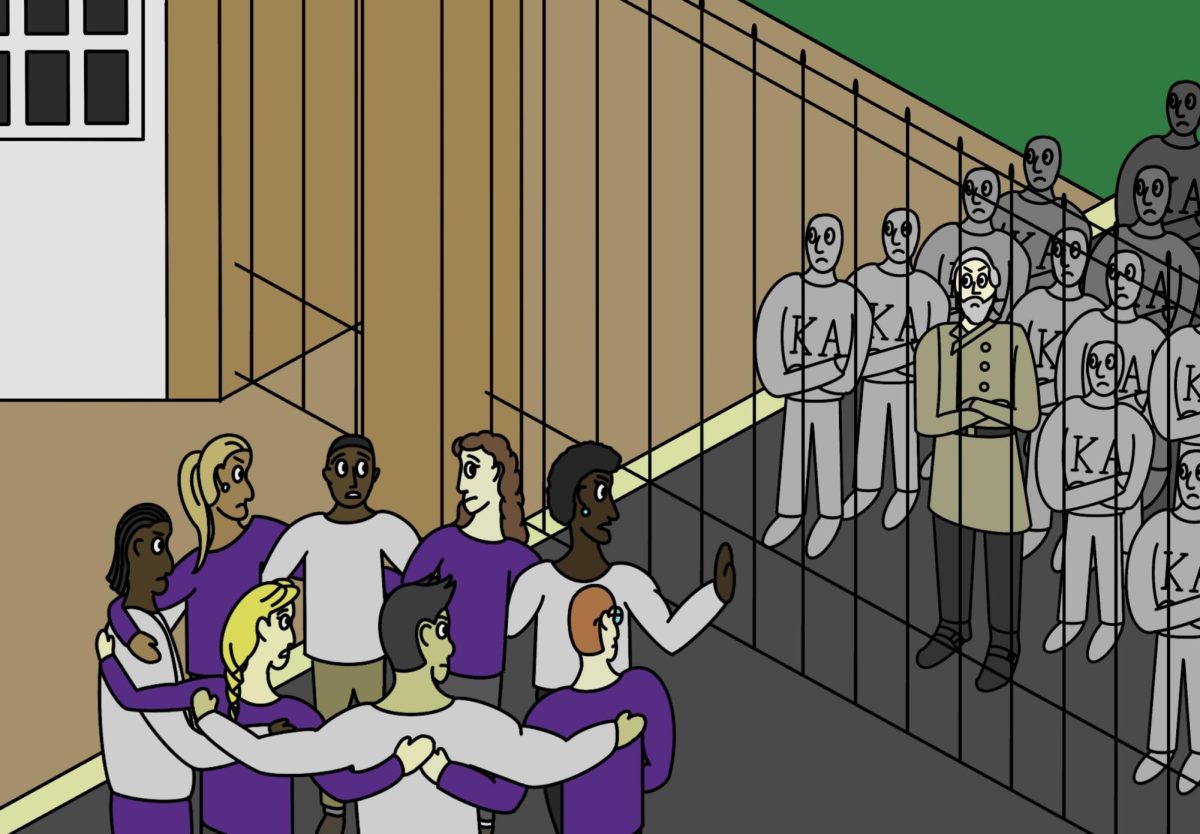

Consider: Men exist in social arenas such as politics or high finance. Women exist in domestic ones: essentially, the home. Men are symbolized by the mind and think reasonably and logically. Women are symbolized by the body and are emotionally reactive. Men are the arbiters and creators of culture, where women are left with the natural world.

It’s not a secret that we live in a world where men are graded as superior to women, and there’s nothing unique about a movie that reports the same thing.

Thus, no one should be surprised that a film financially backed by rich heterosexual men about socio-politically elite heterosexual men is thoroughly patriarchal. We exist in a male-dominated capitalist heterosexual society: it’s incredible that any film fights patriarchy.

The Ides of March tells the stories of people behind Mike Morris’ (George Clooney) campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. Stephen (Ryan Gosling) is the junior campaign manager; Molly (Evan Rachel Wood) is interning with the Morris campaign in Ohio.

Stephen and Molly are clear character foils. Both of them make major mistakes which could torpedo Morris’ campaign. Both of them tell superiors that they’ve made a mistake; their superiors tell them that in this arena, you only get one chance. And then they veer in different directions.

We dramatically discover that Morris impregnated Molly after the Iowa caucus. Stephen, who is having sex with Molly, finds out and helps her get an abortion. While Molly is undergoing her last act of loyalty to the campaign, Stephen is fired from the campaign by his mentor, Paul (Philip Seymour Hoffman) for an unrelated case of disloyalty. Subsequently, he doesn’t pick Molly up from the clinic. Molly takes some alcohol with her medication and dies; Stephen turns his fortunes around by using Molly’s pregnancy as leverage. He blackmails Morris into firing Paul and making him the senior campaign manager.

To recap: Molly kills herself because she’s a woman. Stephen survives and thrives because he’s a man.

Molly transgressed by entering the political realm. She would have done better to have left it to the men. Molly reacted emotionally to what she perceived as total abandonment. Stephen had, after all, fired her from the campaign and told her that the sex they were having didn’t imply affection. Or perhaps we could blame her body. If she hadn’t succumbed to the weakness of sexual activity, she wouldn’t be so harshly punished for violating the rules.

Stephen, on the other hand, transgressed when he gave in to emotion (only women do that). But when he takes a cold-blooded stand for his political life, he comes through with flying colors. As a man, he was born to play politics on and off the camera, and he takes advantage of Morris’ bodily (read: womanly) weakness. By doing so, he ensures himself a high-paying, high-profile job.

In short, he overcomes any womanish tendencies to accede to a man’s rightful place. If he loses his soul along the way, then that’s the price he pays for not acting manfully throughout.

The Ides of March is just one film among many that falls into these simplistic binary traps. It doesn’t mean that the film’s quality diminishes, but the overt messages of patriarchy remain. And from my seat, they look like spaghetti sauce spilling all over a wedding dress.