Furman is one of those colleges where, on any given day, more people frequent the library than the dining hall. (I made up that statistic, but it certainly feels right, doesn’t it?) I’ve written more papers than I care to remember in the 24-Hour Room, so I’ve spent a lot of time looking at the façade of our truly excellent library. Every time I walk in, I’m jarred by the school’s motto hanging above the main entrance: Christo et Doctrinae, “For Christ and Learning.”

Furman University was associated with the Southern Baptist Convention until 1992; there are students on campus who weren’t born when the school split with the Baptists. The separation, as described in wording approved by Furman’s Board of Trustees, was caused by the university’s need “to preserve its values in a religious atmosphere that had become highly combative and increasinglyrestrictive.” That’s as good a reason as any and better than some to sever ties. However, on this same Board-approved page, Furman lays out an oddly contradictory worldview.

We’re told that the university appreciates things like “diversity,” “freedom of inquiry,” and the “freedom to look for truth wherever it is to be found.” But we’re also a university that “has sought to remain faithful to its Judeo-Christian heritage,” looked to hire professors evincing a “life of faith” and “sympathetic awareness of Furman’s traditions and purposes.” The statement that “Furman is a learning community where faith is cherished but not coerced” says it all.

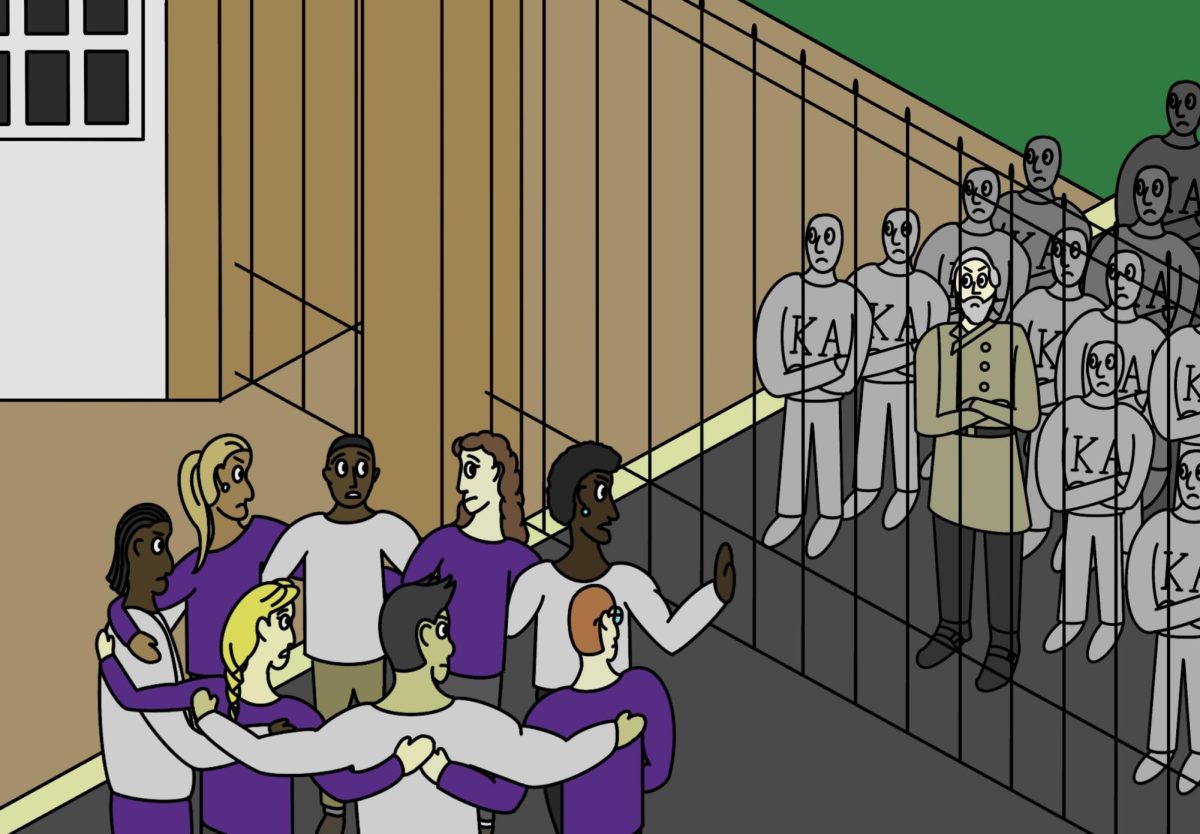

The university isn’t going to force the faculty to sign statements of faith and they’re not going to keep SoFI from meeting. But nowhere on that page do they claim to cherish agnostics or atheists. Heck, we’ve seen the preference for “Judeo-Christian” thought: if your religion didn’t come from Palestine, don’t expect to be cherished quite so much. The whole page, quite simply, reeks of “more equal than others.”

Though Furman is a private university and not strictly bound to the First Amendment the way that, say, the federal government is, we could learn a lot from Justice William Brennan’s dissenting opinion from the 1984 Supreme Court case Lynch v. Donnelly. In it, he says that the motto of the United States, among other things, is “protected from Establishment Clause scrutiny chiefly because they have lost through rote repetition any significant religious content.”

There’s something to that. Christo et Doctrinae has been our motto for a very long time now; also, how many times have you gone into the library and hardly noticed it staring at you above the doors? But Brennan noted also that the mere existence of a motto like “In God We Trust” (or Christo etDoctrinae) is enough to create an atmosphere of “religious chauvinism” that the Establishment Clause exists to curtail.

In other words, even though something like Christo et Doctrinae isn’t actively vindictive or pernicious, its mere existence is potentially oppressive to those who do not believe in a Christ.

As Furman plans to expand, no doubt to turn its strong regional reputation into a strong national one, we need to start expanding our appeal. We have spent two years considering global citizenship and spent the year before focusing on Asian Studies. These are good steps, but they’re also transitory. Our motto, which speaks volumes to Furman’s regional insularism, has stuck with us throughout and looks to be set for years to come. If we really want to start actively competing with universities whose (translated) mottos are things like “Truth,” “Light and Truth,” or “The wind of freedom blows,” a good place for us to start is emulating their stated foci.

Are the opinions and diversities of people who don’t fit into the normative scheme going to get swallowed up or be devalued simply because they’re different? Are they going to be cherished, or will they have to settle for merely not being coerced? As long as Christo et Doctrinae is the motto of Furman University, the visage we show to the world will certainly look to be one of more equal than others. If our university truly wants to pursue things like diversity and finding truth where it is to be found, the message from the top can’t be one that suggests we restrict our focus.

I look forward to the Strategic Planning Committee’s thoughts on our religious future, and I hope that the changes made for the better will include a change in our motto.