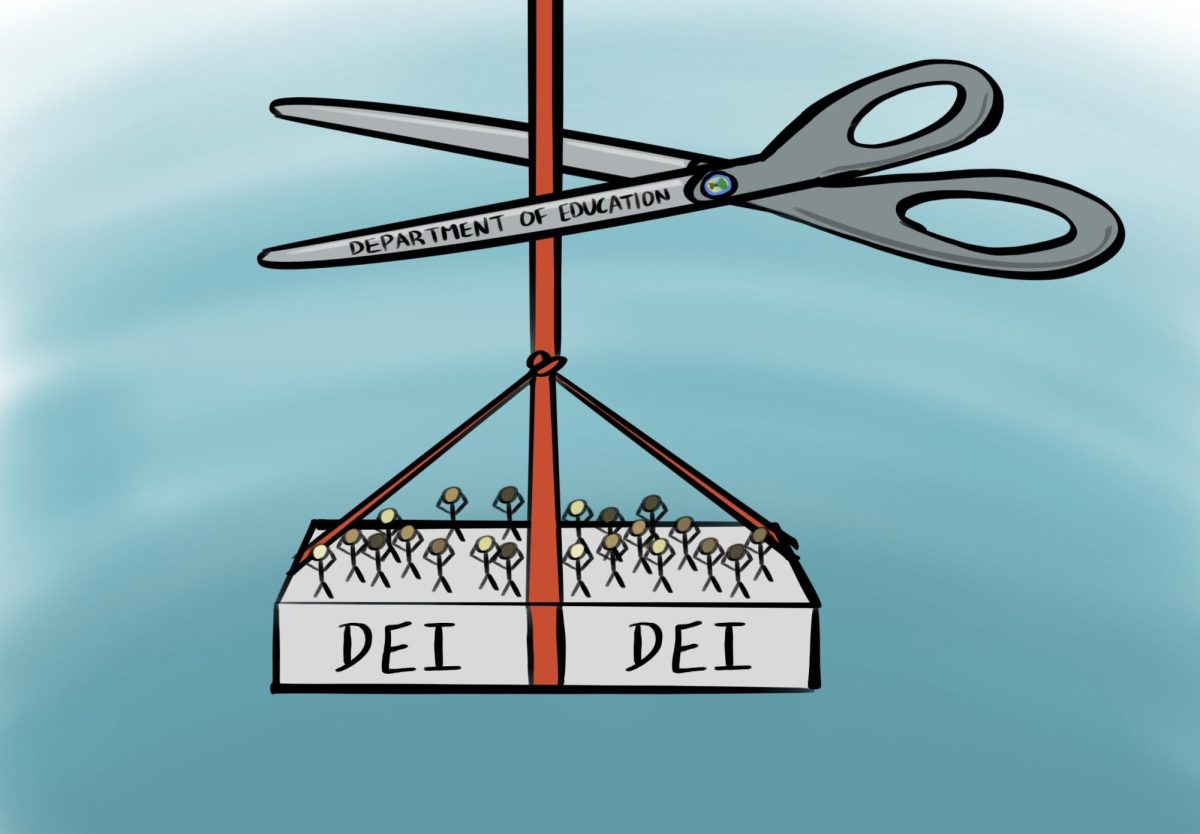

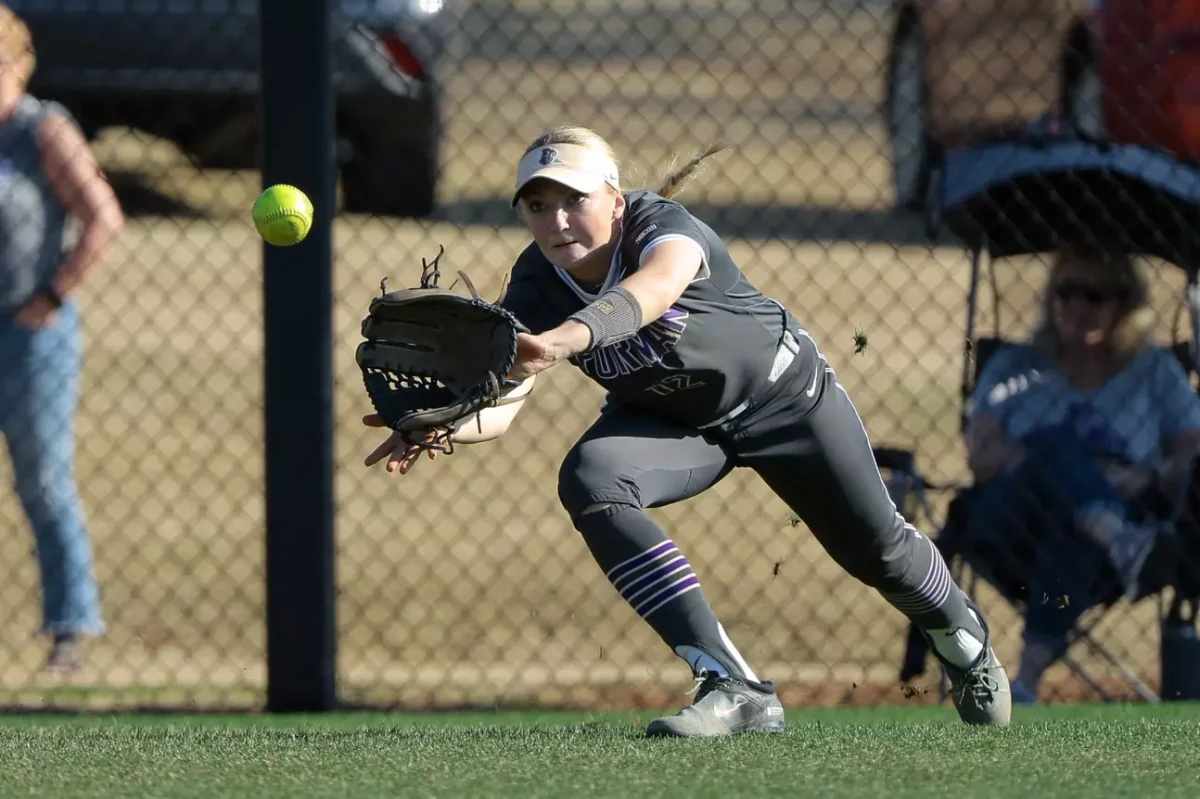

Throughout my time at Furman, I have involved myself with various types of advocacy work, which is aimed at elevating the voices and status of underserved, marginalized or otherwise disadvantaged people. As of late, I have noticed some trends in student activism that I would label as potentially harmful, ineffective and, at times, performative.

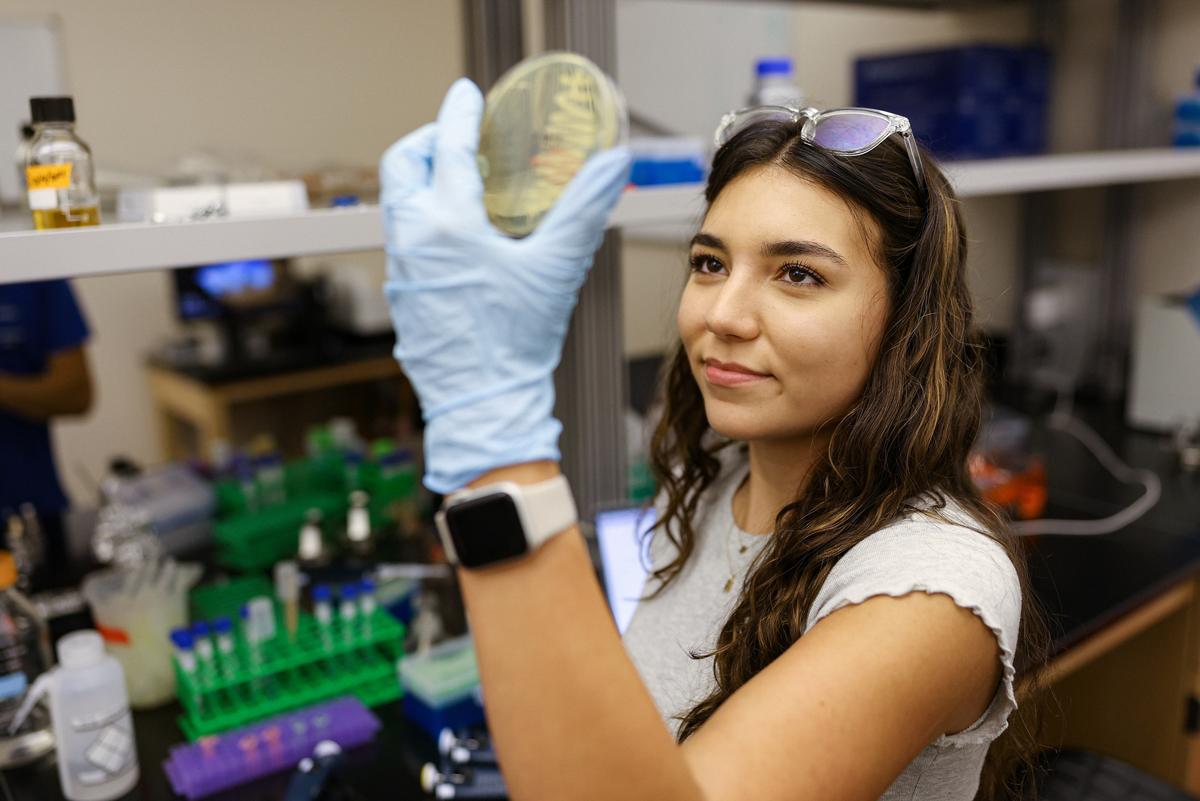

My understanding of advocacy and the way I have engaged in it has transformed over the last four years. Some semesters, my advocacy involved helping organize protests and educational events on campus, mostly through my leadership in the Furman Justice Forum, of which I am currently the president. This semester, my work has taken multiple forms, but my main focus has been preparing a group of students to lobby Congress in Washington D.C. this month. Given my experience, I would like to highlight some issues with advocacy at Furman and provide advice on how to be an effective advocate.

Justice work requires open-mindedness. Believing that oneself is all-knowing, even with the most honorable of intentions, often leads to the silencing of others, which is inherently unjust. I’ve observed this behavior on our campus, with some students attempting to speak for groups which they do not belong to. Lacking the humility required to learn from others can prevent the generation of true justice if the goals of activists and the group being advocated for are out of alignment. Activism, in its true form, is inherently caring and requires activists to care for people in real, sustainable ways rather than fleeting ways, which requires that activists listen to those they seek to advocate for.

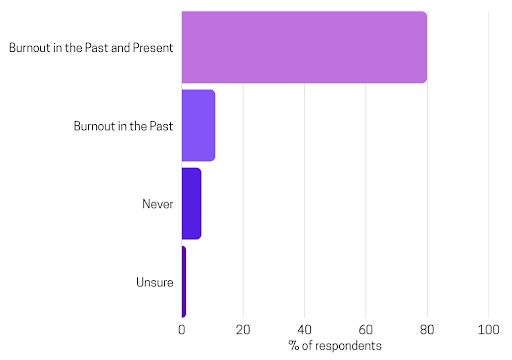

Repetitively, I’ve noticed students who are beginning to engage in activism attempting to do so alone or without much collaboration. Advocates must be supported by a community of people engaged in similar work, as people often lose motivation to advocate if they lack support. This has certainly been the case for the Justice Forum in years past — we are less effective when we are not adequately supporting one another, and we maximize effectiveness when we work as a community. This work is difficult, and it is reasonable that people will become worn down. So, this work requires community, allyship and special care for those impacted most profoundly by injustice.

I’ve also noticed a greater focus on public forms of activism and a disregard for others on our campus. It is important to remember that activism exists in many different facets, some are public-facing and others occur behind closed doors. They are all crucial. If individuals only highlight work which is visible, or perhaps easily Instagrammable, individuals risk disempowering many advocates and promoting performative activism.

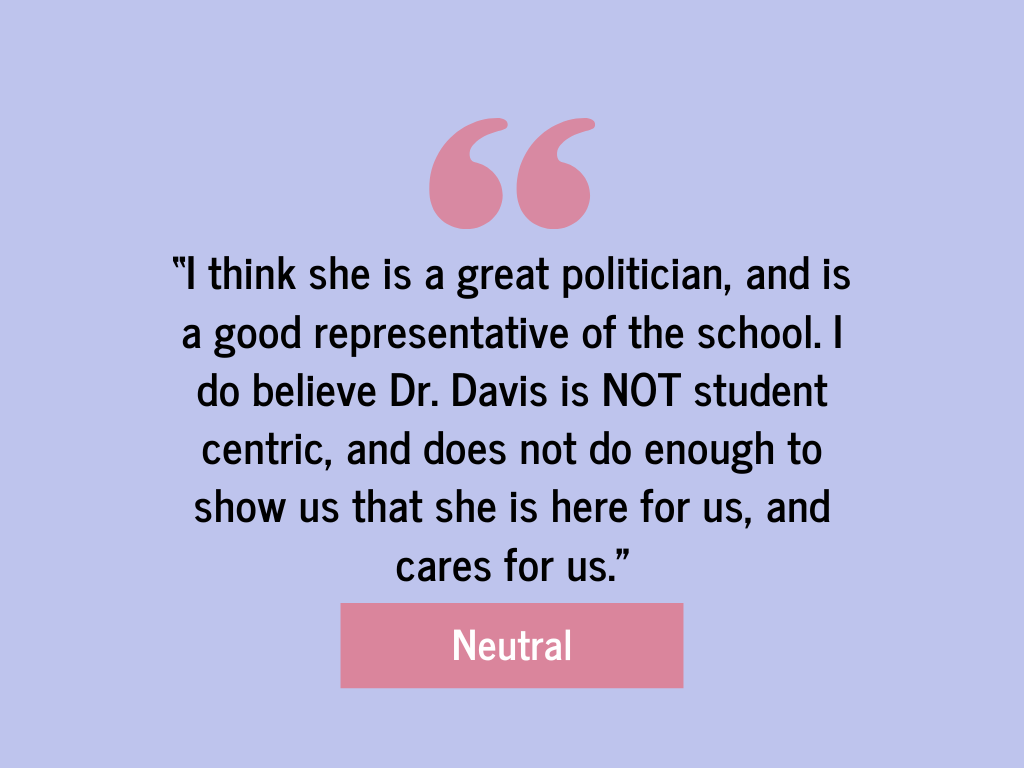

In addition to advocating for marginalized groups, activists must advocate for one another by being fair and realistic in our expectations of each other. One myth in activism is that advocates must be perfect. This has manifested on our own campus through the disregard of student leaders, particularly those of marginalized identities, after making choices regarded as faulty. This behavior disempowers and puts pressure on student leaders. In a just world, activists are allowed to be human, make mistakes and learn from them. Those who continue to perpetuate harm should be held accountable. However, people should be given opportunities to grow when they make mistakes. After all, college is a time of immense growth for many.

My suggestions thus far have been intended for people already participating in advocacy. However, I would also like to provide advice on how to get involved in this work.

For those interested in activism, I suggest starting by considering the following questions: What is the desired goal of your action? Who is your work empowering? Who might it be disempowering? What is something you can do that you will feel driven to continue doing? What is it you are truly passionate about? (Tip: one person can’t solve every issue; find the one(s) you have the most energy for.)

One avenue for advocacy work is through taking advantage of educational opportunities. Some examples include participating in a workshop that teaches advocacy skills, attending a talk or taking a class related to an issue you are interested in, reading, and listening to the stories of those who are impacted by particular injustices.

Once you have found an issue you are passionate about, there are a multitude of ways to advocate for it. Activism can take the shape of protests, voting and lobbying people in positions of power, whether it be at Furman, state governments, or the federal government. Additionally, informing others about issues is a form of advocacy, and it can cause other people to join this work. If you feel called to share, this can include your personal story and experiences.

In addition to different forms of activism, there are different levels of advocacy one can engage in. You can find groups already doing work you support and advocate with them by volunteering your time and, if possible, your finances. Formal work opportunities in advocacy can be found in the non-profit sector and within government relations and policy work. Finally, you can be an activist through being an active and caring community member. Recognize and speak on potentially harmful actions done by those in your community — whether the potential harm is self-inflicted or affecting others. In other words, call people out (lovingly) on behavior that could hurt themselves or others. Care for and listen to those around you!

These suggestions are not exhaustive by any means, but these are some of the ways I have found to work towards justice in a sustainable manner. Again, we are all human and shouldn’t expect each other to be perfect or to do all the above action items. Rather, an approach which places focus on community members and wellbeing allows for people to be human and activists. I believe we can all be advocates — and perhaps we all should be.