Prior to my freshman year, I was warned by family and friends alike that I would need to be on my guard in college — that there would be people who would try to push their own agendas on me while working to silence my opinions, should they differ. Based on my high school experience, I believed that Furman would be similarly polarized, with a tangible divide between conservative and liberal students.

My experience, however, has been anything but that. I have made friends from across the political spectrum and have found that in classes, specifically Politics classes, professors do a good job of being objective rather than letting their personal opinions dictate how they teach certain course material.

Furman is uniquely situated within the current landscape of higher education. At many college campuses across the nation, partisanship causes social unrest. Student protests prevent speakers from sharing their beliefs and ideas by shutting down events or even using violent tactics to get their point across. Just last fall, Ivy League colleges were in the public spotlight due to their reactions to student protests regarding the Israeli-Hamas conflict, according to AP News. The most controversy that Furman has faced was a silent protest organized in spring 2023, in response to the speaking engagement of Scott Yenor, and the subsequent op-eds written in the Wall Street Journal debating Furman’s tolerance of free speech.

However, Furman does have a problem — we are a largely apolitical campus. Politics is a taboo subject at this school. Using the latest data available, from 2022, only 19.7% of students voted in the midterm elections, well under the national average of 30.6% amongst the more than 1000 institutions that participate in the All In Campus Democracy Challenge. While the data trends upwards for voter registration, thanks to the hard work of groups like Dins Vote, Furman’s low voter rate is one symptom of political apathy on campus.

If political polarization is the negative extreme of political engagement, then political apathy is the absence of political engagement. We are just over a month away from an election which promises to be close, extremely contentious and have higher stakes than ever. Our campus needs to learn how to have important political conversations without succumbing to the political polarization that plagues broader American society.

To brainstorm how Furman can achieve this goal, I sat down with Isaac Saul, the founder of Tangle News, an independent, non-partisan newsletter. Saul created Tangle because he noticed how strong the information bubble effect is — that is, people will only consume news from outlets that are telling the same story. He saw an opportunity to create a newsletter that provides perspectives from both the right and the left, as well as his own perspective.

Saul’s first recommendation was to create spaces on campus that are designed to bring students from opposing sides of the political spectrum together to engage in civil conversations.

Currently, there are few student groups that are specifically designed to facilitate such conversations or work to bridge the gap between opposing ends of the political spectrum. While the work of the Riley Institute and the Tocqueville Center is important because they host lectures with a diverse range of speakers that open the door to further conversations, Furman still lacks a designated space to hold these conversations. Furman’s introduction of an intergroup dialogue on “Polarization and Political Identities” is a very important step in the right direction, but as it is currently only open to twelve students, it won’t reach the larger student population.

Groups such as BridgeUSA are at work in high schools and universities around the United States to help create intentional environments that foster conversations that are designed to educate students about viewpoints that they do not agree with. A student group that engaged in similar work would not only be well-received on campus, but also provide a much-needed space for students to better understand diverse viewpoints.

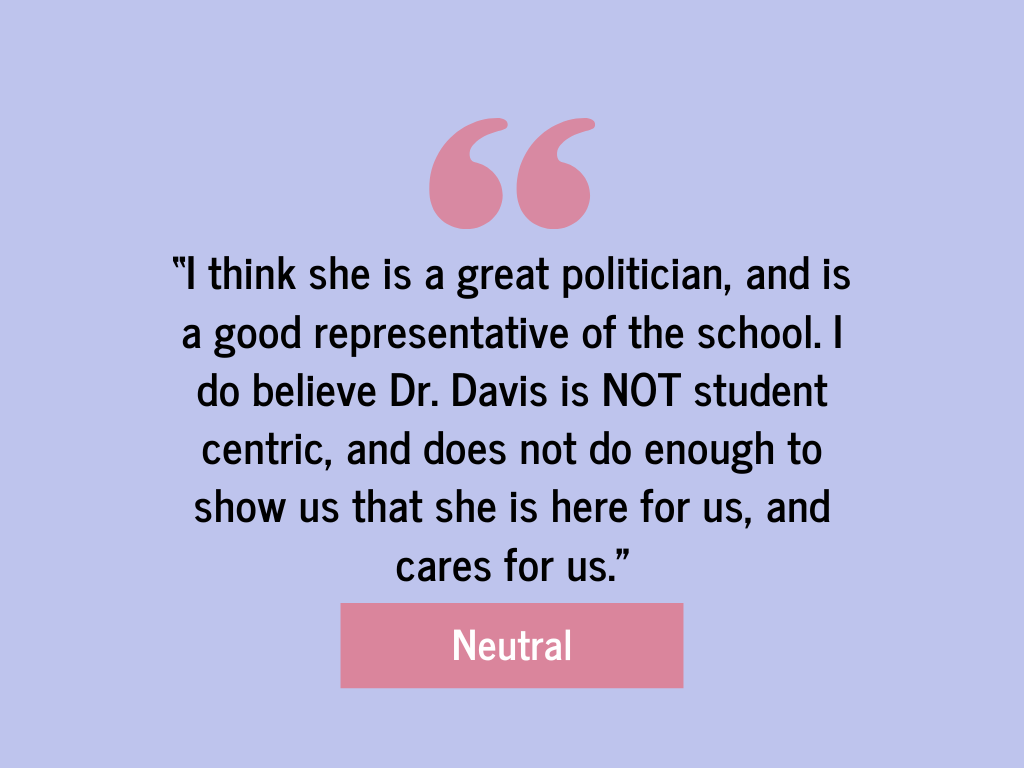

Saul also recommends we separate the idea that has been ingrained in the American psyche that being non-partisan means being apolitical.

“To me, being non-partisan doesn’t mean not having an opinion, and it doesn’t mean not having feelings,” believes Saul. “It is really about being open minded and not being tribal and not playing for a specific team.” Saul advises people to recognize that good ideas, which have value and deserve attention, exist across the political spectrum.

Holding strong political opinions can oftentimes make us want to label the other side as uneducated at best and immoral at worst. However, being truly non-partisan means navigating the tension of holding your own personal, sometimes strong, views while acknowledging that other opinions exist that have valid foundations. The difficult yet crucial task before us is to move from being apolitical to being politically engaged while remaining non-partisan.

This begins first and foremost by registering to vote and making a plan to either vote in-person or by mail this November. More broadly, students should seek out opposing opinions, ideally by creating an intentional space on campus where diverse and nuanced political conversations can take place. Moving beyond partisanship during this election season is crucial to bridging divides and creating a healthier culture around politics on campus.