20 years ago, Furman English professor Dr. Gregg Hecimovich read the then-recently published “The Bondwoman’s Narrative” by enslaved schoolteacher Hannah Crafts. Seeing as her background was still shrouded in mystery, he took on the task of uncovering the full story of this author. Her narrative was powerful and fascinating, which inspired him to look for her other works. He found that the narrative dated back to 1857, making it the oldest original manuscript in the African American literary canon.

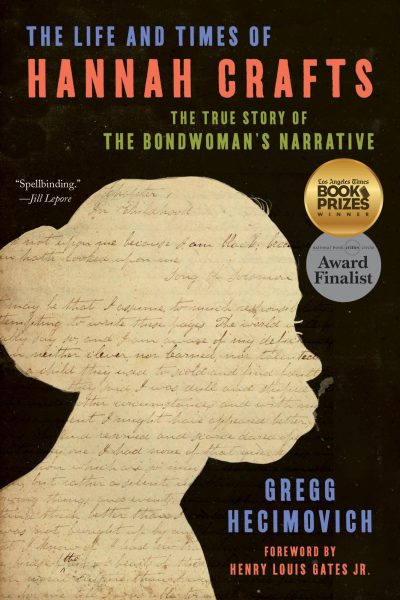

A holograph manuscript, Crafts’ original handwriting was preserved in the narrative. Beyond this document, preserved by literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. until its publication in 2002, nothing was known about Crafts. Thus, Hecimovich set out on two decades of research, uncovering the story behind the first documented female African American author. Hecimovich’s work culminated in his October 2023 biography, “The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts.”

“When you have the actual handwriting, you can see the artistic progression. The research was less about me speaking and more about listening. Because the authority to tell this story has nothing to do with me really,” Hecimovich said.

Hecimovich started his research in Indian Woods, N.C. to find out more about Crafts’ story. With no centrally-gathered records, he found through conversation a rich history of this descended community — a history willfully ignored. He dug through attics, found a high school teacher who was an unofficial repository of the town’s history and had tea with the ancestors of the former enslavers. Through constant travel and patience, Hecimovich pieced together a full story of Crafts’ life.

“It was like a series of Chinese lanterns. Each one lights a part of her life, then another follows,” he said.

Hecimovich discovered that Crafts, who later married and took the last name Vincent, had a high degree of literacy. Immersing herself in a wide variety of literature, Crafts found respite in storytelling and the imaginative freedom it offered during her time in enslavement. Heavily influenced by Charles Dickens’ “Bleak House”, she riffs on this Victorian novel in her narrative, weaving parts of her own story with fictitious elements.

Some of the most powerful passages in the novel are direct responses to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” as well. For example, forced to accompany her enslavers to blackface minstrel shows, she flips the narrative on its head. Her enslaver, Mrs. Wheeler, is forced to wear blackface and beg another white man for a political position for her husband. His degrading response exposes the greed and bestiality of her white enslavers. “If either you or him had possessed a particle of common sense, you would not have asked for it.” (Crafts 168).

“It’s the absolute showstopper of the novel. She completely flips the script,” Hecimovich said.

Hecimovich, as well as other literary scholars, are uncovering the Black Archive – stories “lost” or overlooked in white-centered libraries, he says. These libraries were typically curated by elite families and often overlooked the literature or history written by enslaved individuals. The importance of Crafts’ work lies in the fact that “The Bondwoman’s Narrative” is one of the many lost works written in the antebellum period by enslaved individuals. However, none of those works have been preserved in the original handwriting as Crafts’ was.

Hecimovich’s biography won both the American Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Biography. Now working on a new edition of “The Bondwoman’s Narrative” alongside Gates Jr., Hecimovich hopes to uncover more works from Crafts or other authors like her who have been ignored in literary studies.

“I’m so grateful to be part of this exciting moment. There’s a million dissertations to be written about this one narrative alone,” he said.