Furman University. FU. “Furmie.” Or most commonly, Furman.

These are the names with which we refer to our cherished university. However, many students and Furman community members know very little, if anything at all, about the origins of the name and of the university itself. Ask any student if they know the year the university was founded, and it is quite probable that they will give you a wrong answer (unless, of course, they have been paying attention to the signs at every entrance that indicate the school was founded in 1826). This, while perhaps frustrating, is neither uncommon nor unexpected: you are likely to find similar results if you asked that question at any university. The fact is, most students are completely ignorant of Furman University history. I know, because up until very recently, I was too.

Lately, I have come to understand that this university’s very name reveals the long shadow of slavery, as its founders and early advocates were direct beneficiaries and proponents of slaveholding’s role in society. I was entirely unaware of this piece of Furman history until several weeks ago, as I suspect many others currently are.

However, there are important reasons to learn the history of the school you have chosen to attend. Simply put, the history of your school influences its culture in the present day. The history of an institution, and the journey an institution has taken since its founding day, has a profound effect on that institution and what it values. For this reason, I believe that it is important that all members of the Furman community, both present and past, be aware of the history of our institution, especially when that history is less than savory at times. This is our history — it belongs to us, and we need to be responsible for it.

A Brief Look Into University History

At Furman’s inception in 1826, the school was named the Furman Academy and Theological Institution, and was chartered under the auspices of the South Carolina Baptist Convention. The small school was named for Dr. Richard Furman, the founder and president of the Convention. According to our University website, Furman was “considered the most important Baptist leader before the Civil War.”

Originally from Esopus, New York, Richard Furman moved to South Carolina as a child. He was ordained at the age of 19 after being converted from Anglicanism to the Baptist faith. He volunteered to fight in the Revolutionary War, but instead was directed to devote his efforts to converting loyalists to the Patriot cause. In 1790, he served as a delegate to the South Carolina Constitutional Convention. Beginning in 1787, he also served as the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Charleston. He remained in this position until his death in 1825.

Though initially opposed to slavery, Furman changed his position when he became a slave owner. He eventually became one of slavery’s greatest champions, releasing a pamphlet in 1822 entitled “Exposition of the Views of the Baptists Relative to the Coloured Population of the United States” in which he outlined the religious and intellectual arguments for slavery. The pamphlet was written in response to the Vesey Conspiracy, an unsuccessful slave rebellion led by a free black Methodist leader, in order to reassure slaveholders that Christianity was indeed congruous with slavery. Pro-slavery Southerners would use his arguments for the next four decades. He wrote,

“The result of this inquiry and reasoning, on the subject of slavery, brings us…very regularly to the following conclusions: That the holding of slaves is justifiable by the doctrine and example contained in Holy writ; and is; therefore consistent with Christian uprightness, both in sentiment and conduct. That all things considered, the Citizens of America have in general obtained the African slaves, which they possess, on principles, which can be justified…That slavery, when tempered with humanity and justice, is a state of tolerable happiness; equal, if not superior, to that which many poor enjoy in countries reputed free.”

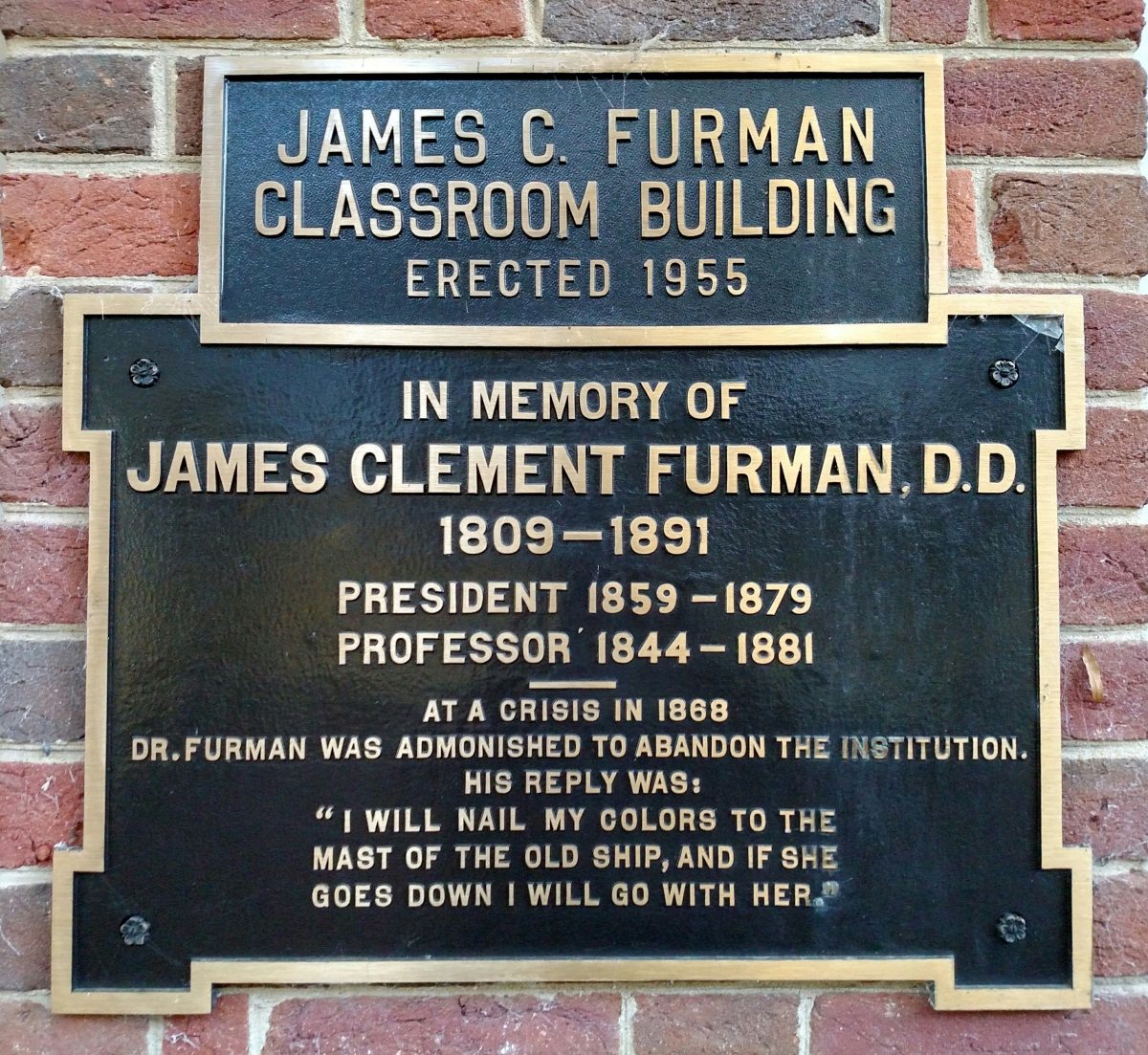

Richard Furman’s son, James C. Furman, for whom Furman Hall is named, was born in 1809 and joined the school in 1844 as a professor. A year later, he became the head of the institution, and when the school was rechartered as The Furman University, he became the first president.

Like his father before him, James C. Furman was a slave owner, at one point owning as many as 55 slaves. He was also a steadfast supporter of the Southern Cause — specifically, the right to own slaves. In the month before he represented Greenville at the Secession Convention and subsequently signed the Ordinance of Secession, Furman authored a “Letter to the Citizens of the Greenville District” that outlined what was to come with Abraham Lincoln as president: the abolition of slavery.

“[E]very negro in South Carolina, and in every other Southern States, will be his own master; nay, more than that, will be the equal of every one of you. If you are tame enough to submit, abolition preachers will be at hand to consummate the marriage of your daughters to black husbands! Nay, nay! We beg pardon of South Carolina women for such a suggestion.”

The Northerners, he wrote, had “A false opinion, which contradicts common sense, contradicts all history, contradicts the Bible…That false opinion is, that every man is born free and equal.”

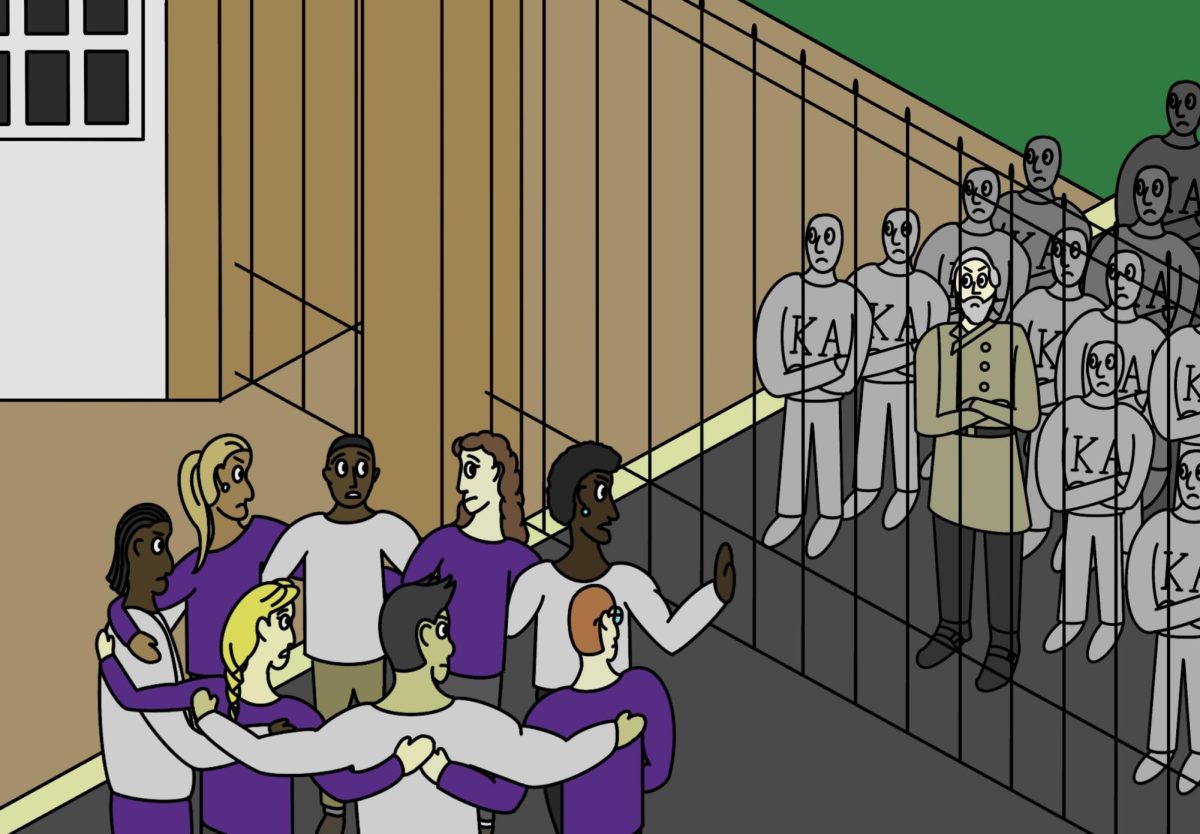

Clearly, both Richard and James C. Furman were not just ordinary slave owners. They were men with public platforms, which they used to advance the institution of slavery itself. While they devoted themselves to furthering education and supporting what is now Furman University, they also denied the right of certain men to be free. We still honor these men today, simply by the fact that our university bears Richard’s name and our humanities’ building bears James’. Ostensibly, the reason these men are still honored is because of their contributions to the University.

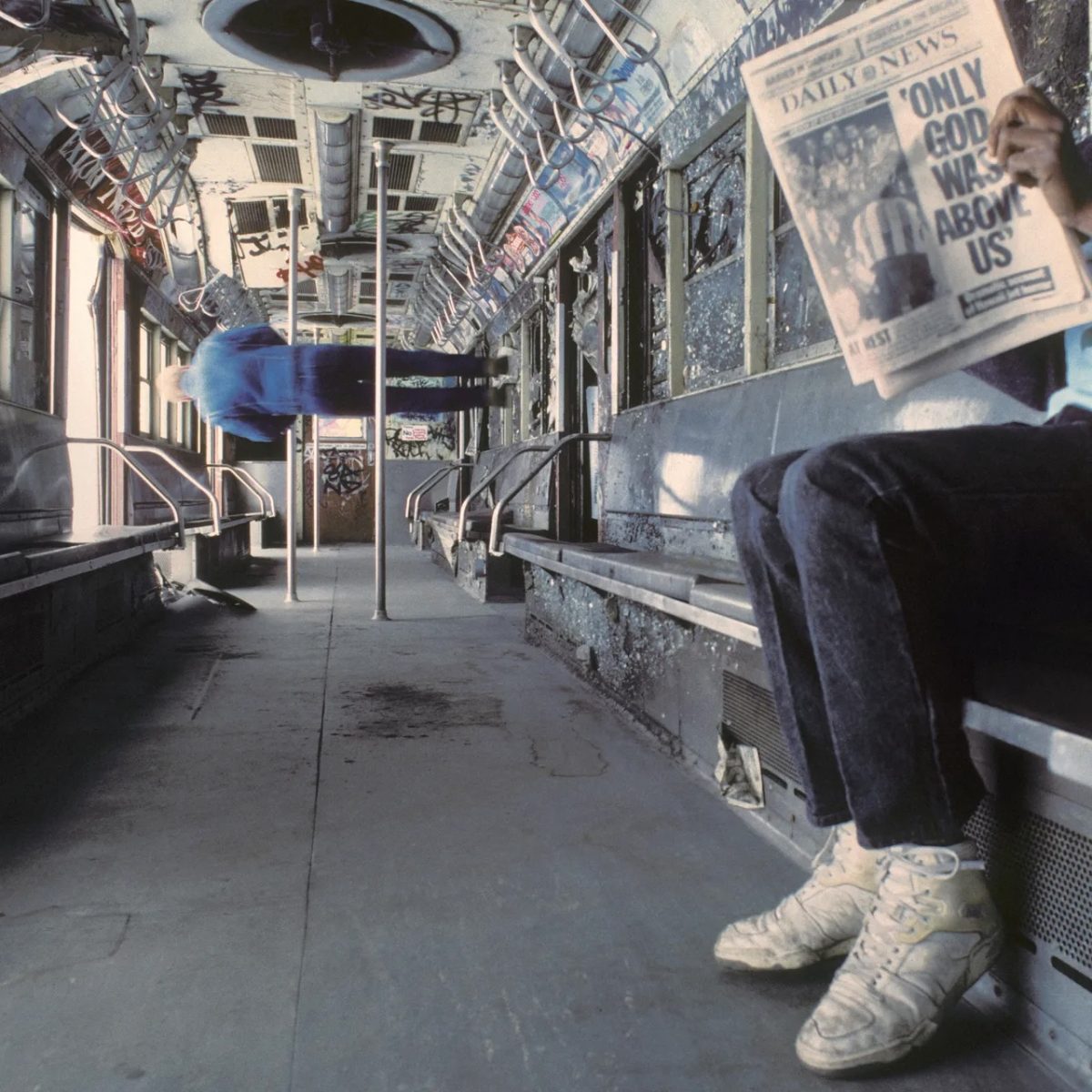

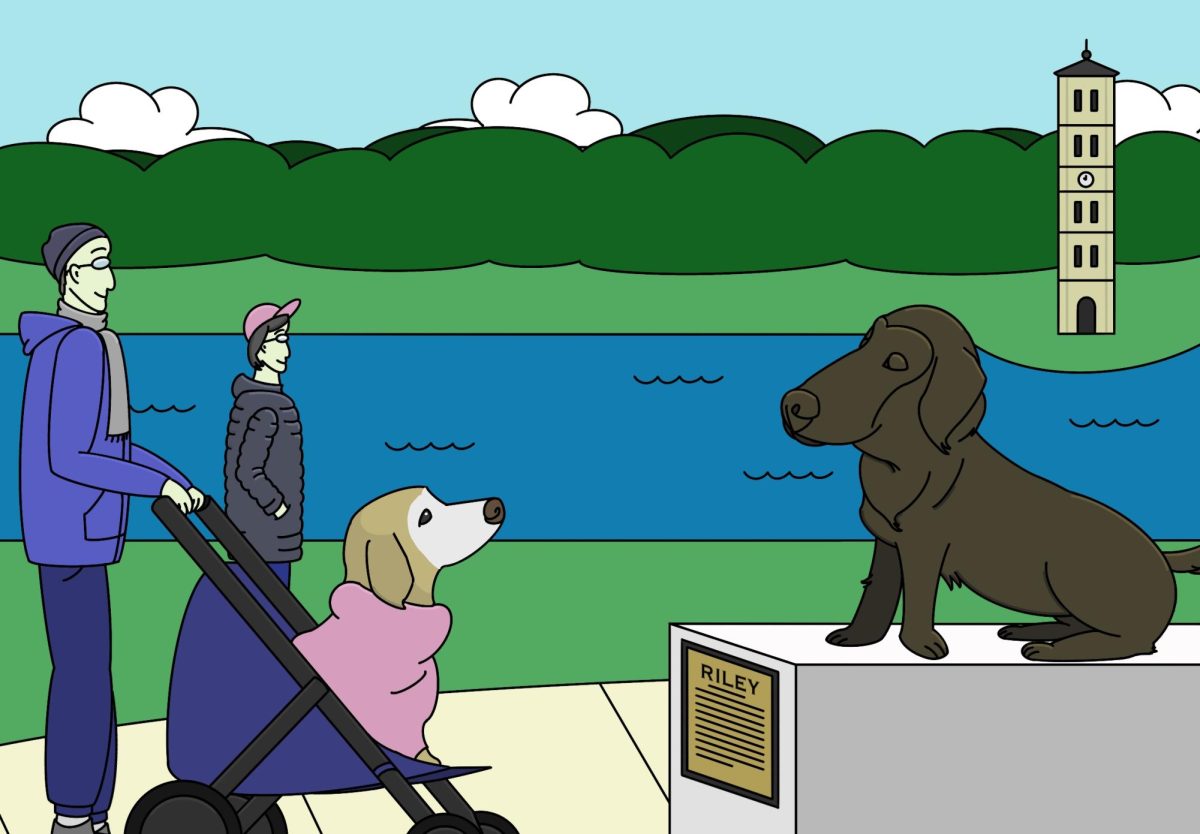

Yet, when we honor these men, there is no mention of their complicated past, i.e. the fact that they owned slaves and defended slavery to the utmost. If you read the plaque outside of Furman Hall that dedicates the building to James C. Furman, you would most likely walk away from it thinking that James C. Furman was a thoroughly commendable man with an intense dedication to Furman University. It reads, “I have nailed my colors to the mast and if the vessel goes down, I will go down with it.”

If you visit the Furman University website, there is still preciously little to be found concerning the Furmans’ slaveholding. The webpage “Our History” makes no mention of it, and neither does an interactive historical timeline that specifically introduces both Richard and James C. Furman. Only if you search through Richard and James C. Furman’s online letter archives, held in Duke Library’s Special Collections and University Archives, do you find mentions of slavery.

Though the history is well hidden, it is still there. These men were vital to our fledgling university, and we still bear and honor their names. In hiding parts of these men, we are denying part of our history.

Examining Our Peers: Clemson and Georgetown

Not all — in fact, very few — American universities and colleges have unblemished histories. There is nothing that can be done about this; nobody can change history. However, recognizing and admitting to unpleasant parts of one’s history is the only way that true healing can begin. The scars are still there, waiting; an institution can choose to face them head on, or sweep them back under the rug from whence they came.

Two universities that have recently had to face their past come to mind as examples. The first, Clemson University, is one with which we are likely all familiar: in the past year, Clemson faced a scandal over the name of their main academic building, Tillman Hall. Tillman Hall was, and still is, named for Benjamin Tillman, a South Carolina legislator and virulent racist who openly used racial slurs while advocating for the killing of blacks. Forced to face Clemson’s less than picturesque past, the Clemson Board of Trustees ultimately chose to change nothing, and released a statement saying that renaming the building would be nothing but a “symbolic gesture.”

Clemson professors fought back, writing in a statement that “Renaming Tillman Hall is more than symbolic, it is real. It is an affirmation that hatred, represented by actions or symbols, has no place in the Clemson University community now or in the future. While renaming Tillman Hall will, in isolation, fail to secure a sustainable and more inclusive future for the University, it is far more than symbolic. It is an affirmation that honoring those whose station and legacy were achieved in significant measure via the vilest actions of intolerance has no place at Clemson University now or in the future — even as the history, university-related role and scholarly study of those same individuals must have an indelible role in our educational mission.”

The second example, Georgetown University, may be less familiar, but no less poignant. In 1838, in an attempt to keep the struggling university afloat, its Jesuit leaders sold 272 slaves to plantations in Louisiana, a sale worth $3.3 million in today’s dollars. The university made no attempt to keep the families together, though they had been instructed to do so by the state of Maryland.

For almost two centuries, Georgetown struggled with this terrible history. However, this August, Georgetown’s president, Dr. John J. DeGioia, announced that it would be taking steps to atone for the university’s dark past. Georgetown has formally apologized for its participation in the institution of slavery, and has promised to create an institute for the study of slavery, erect a public memorial to the slaves whose labor benefited the school, rename two campus buildings and offer preferential admissions status to the descendants of the 272.

Speaking to a crowd of students, faculty members and descendants, Dr. DeGioia faced his institution’s history directly.

“This community participated in the institution of slavery,” he said. “This original evil that shaped the early years of the Republic was present here. We have been able to hide from this truth, bury this truth, ignore and deny this truth…As a community and as individuals, we cannot do our best work if we refuse to take ownership of such a critical part of our history. We must acknowledge it.”

Why This is Important: Leaving Our Own Legacy

The slaveholding history of our university’s founders is neither unique nor unusual for southern schools founded in the antebellum South. We can neither deny nor erase this history, nor should we. However, it is important that we be aware of this history, as to do otherwise is a great disservice to those who suffered under the institution of slavery and to ourselves. We must be aware of it because its legacy trails through not just the Civil War and Reconstruction, but through the Jim Crow Era, through Civil Rights in the mid-20th century and beyond. Its legacy also does not end with Furman University’s desegregation in 1965. While the University has changed immensely since the Civil War, specific renunciations of its founders’ attitudes towards slavery have not been present in the hundred and fifty years since, as far as I can tell.

As long as James C. Furman’s name stands attached to the Humanities building without addressing his part in slavery, and as long as the Furman website fails to mention Richard Furman’s and James C. Furman’s advocacy for slavery, then Furman is whitewashing its history. Furman needs to face its past in a responsible manner that properly serves the historical record and does not seek to place marketing aims over admitting past wrongs.

In regards to Furman Hall, adding another plaque that offers a more balanced view of James C. Furman may be one step we can take. “Think about the legacy we would leave if we added another plaque. That means that every person visiting [Furman Hall] would say, ‘These people aren’t running away from their past. They are addressing it, and they are addressing it in a very responsible way,’” said Furman historian Dr. Courtney Tollison.

As Georgetown historian David J. Collins wrote earlier this year, “Slavery is our history, and we are its heirs. America would not be America except for its deplorable history of slavery. There will be no ‘liberty and justice for all’ until we understand that.”

Furman has faced immense challenges and experienced tremendous change throughout its history. Not all of this history is necessarily admissions fun fact appropriate. However, that does not mean that it should be ignored. In order to move forward, we must look back. Let us take action to reconcile our history with where we currently are as a university, so that we might leave a better legacy for generations of students to come.