Qui tacet consentire videtur, ubi loqui debuit ac potuit is the phrase of the day.

“Qui tacet consentirevidetur” essentially means that silence is consent. As scary as that is, ”ubi loqui debuit ac potuit” is terrifying: roughly, “he ought to have spoken when he was able to.”

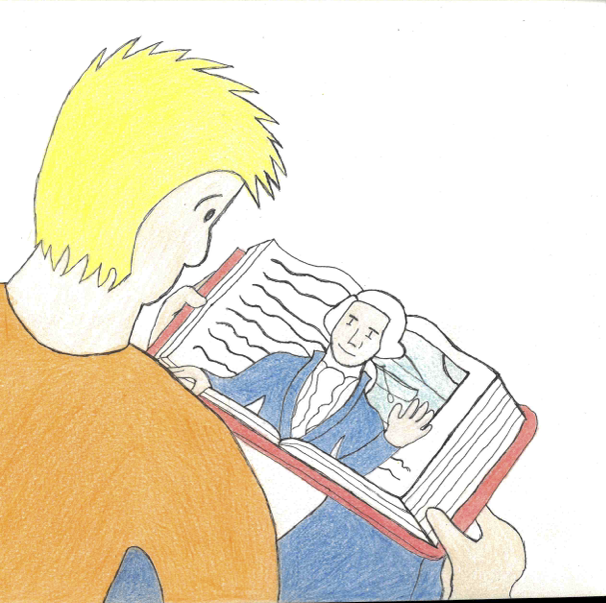

One of the greatest manipulators of public opinion in American history proved his uncanny skill to do so with a single speech in late 1969. President Richard Nixon was not the first person to use the phrase “silent majority,” but his usage of it in that speech brought national attention to its implications. His address, which came about due to increasing criticism of the Vietnam War, suggested that despite the loud and attention-grabbing protests, most common people gave his policies their unvoiced support. Whether or not most of the country really agreed with Nixon is unimportant. What matters is that so many were quiet in the first place.

Politicians past and present float on a peaceful current of tacit approval. For ordinary citizens, tacit approval is a hand forcing their heads underwater.

Many of us probably don’t realize the extent of our national silence. Our short attention spans and our belief in fundamental institutions mean that we rarely demand change or accountability. Did our blood boil because of Abu Ghraib? I doubt it. Amnesty International still condemns American POW camps in the Middle East. Were we shocked by My Lai? Not enough to care that only William Calleywas convicted of any wrongdoing in the massacre of Vietnamese civilians. Were we aghast because of our conduct in the Philippine-American War? Probably not. If you’ve heard of it, congratulations on being a history major.

So maybe we were outraged briefly by the various war crimes undertaken by Americans. We’ve punished some names and strode on, patting ourselves on the back for being just. In the words of Colin Powell, these crimes “are still to be deplored.” Hating misdeeds is cute. That puts the breath of life back into the lungs of the 504 murdered at My Lai; it resurrects 1.4 million Filipinos whose deaths correlate to the Philippine-American War. Truly hating injustice doesn’t mean condemning the past; those who hate injustices of the past work to ensure they cannot happen in the present or future.

It’s not as if the military is the only offender here, and it’s extremely unfair (not to mention stupid) to pretend otherwise. Every generation has major political scandals to look back on wistfully; our parents have Watergate and Iran-Contra, we have Scooter Libby and Halliburton. These are the ones that command attention on 24-hour news networks, the ones that have international ramifications. Then there are state scandals, there are municipal scandals. It isn’t that the days of honest politicians who had their constituents’ best interests at heart are bygone; it’s that they never existed. We have consented to them, we take it for granted, we slap individual wrists and never look at the system that allows those corrupt individuals to flourish.

Silent consent is never more obviously subtle than when we focus our hindsight on civil rights movements. Forty-eight years after “I Have a Dream,” it seems self-evident to us that racial segregation is a great moral wrong that actively does evil. Forty-eight years from now, when LGBTrights are the norm (though to suggest that they’ll be fully realized is to suggest that the rights of African-Americans or women are fully realized), your grandchildren will ask you how people could have failed to understand that sexual preference was unimportant.

Your answer will echo the answer of your grandparents’ when you asked them how skin color could have mattered so much in their time. “I don’t know,” we’ll say (just like they did), “but I should have spoken when I was able.”

Know that to consent with silence is to side with power. If you are not in the streets, if you are not writing in public forums, if you are not daring in speech with your peers, if you are not active in debate with strangers, then you belong with those people drowning in the murky waters of tacit approval.